BANFF – Parks Canada is taking dramatic steps to eliminate a deadly fish disease from Johnson Lake in a bid to protect a threatened trout species in the nearby Upper Cascade River watershed.

The federal agency will partially drain the Banff National Park lake over the course of the winter to remove any remaining fish that may be infected with whirling disease, which causes physical deformities and sometimes death in fish.

Parks Canada officials say whirling disease has been successfully eliminated from a creek in Colorado in the United States to protect a native trout species there, but the work at Johnson Lake will be a first for Canada.

“It’s not that we hope to eradicate whirling disease in western Canada; we know that’s not feasible with the current technologies, but we believe we can from Johnson Lake,” said Bill Hunt, resource conservation manager for Banff National Park.

“The concern is the proximity to the Upper Cascade River, which flows into Lake Minnewanka and the importance of that area for westslope cutthroat. The Upper Cascade has some of the only remaining pure populations of westslope cutthroat trout.”

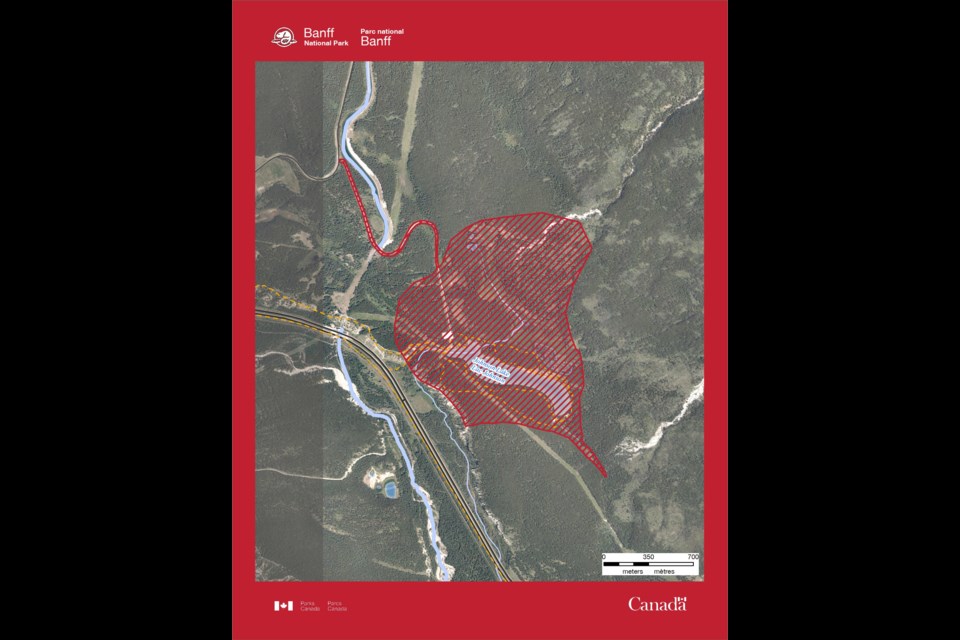

Johnson Lake, an 18-hectare lake located about 11 kilometres from the Banff townsite popular for swimming, paddling and fishing, was the first place in Canada where the disease was detected.

Since its discovery there in 2016, whirling disease has been confirmed in many other creeks and rivers throughout Alberta, including the Bow, Oldman, North Saskatchewan and Red Deer watersheds.

Named for the circular and erratic swimming patterns of infected fish, whirling disease affects several fish species in Alberta: bull, cutthroat, rainbow, brown and brook trout, as well as mountain whitefish. Both cutthroat trout and bull trout are listed as species at risk.

The disease is caused by an invasive parasite known as Myxobolus cerebralis, introduced from Europe to the Unites States in the 1950s. The parasite is spread through contact between fish and a freshwater worm.

Without these two hosts, the parasite cannot complete its life cycle and will die without multiplying.

The parasite penetrates the head and spinal cartilage of these fish. Infected fish swim erratically and have difficulty feeding and avoiding predators. Other signs of the disease include darkened tail, twisted spine, or deformed head. In severe infections, whirling disease can cause death.

Hunt said although nearby Two Jack Lake and Lake Minnewanka are currently free of whirling disease, there are concerns that birds such as loons and ospreys hunting fish could transfer the disease from nearby Johnson Lake.

In addition, he said another concern is that boats or fishing equipment that comes into contact with water or mud at Johnson Lake can potentially be a vector for transmitting whirling disease to another area.

“If fish in Lake Minnewanka were to become infected, there are concerns they could move up into the entire Cascade River watershed and come into contact with westslope cutthroat trout,” said Hunt.

Conservationists with Bow Valley Naturalists say they are supportive of Parks Canada’s efforts to eradicate whirling disease from Johnson Lake.

“Given the popularity of the lake and how easily visitors could become unwitting hosts in the spread of the disease, Parks Canada’s experimental efforts are warranted,” said Reg Bunyan, vice-president of Bow Valley Naturalists.

“A significant amount of time and money has already been spent on eradication efforts and this is indicative of just how hard it is to eliminate an invasive species, or disease, once it’s become established.”

To date, Banff has been relatively geographically isolated from the myriad of aquatic invasive issues to the south and east of Alberta, Bunyan said.

“Whirling disease is just one of a number of threats facing our aquatic systems, which is why provincial and federal government agencies are placing so much more attention to inter-provincial boat inspections, launch restrictions and public aquatic education,” he said.

Recent results of whirling disease research studies in Montana, California, and Colorado indicated it might be possible to break the life cycle of the parasite in some situations.

The disease was eliminated in Placer Creek, a tributary of Sangre de Cristo Creek in Colorado’s San Luis Valley, home to native Rio Grande cutthroat trout whose numbers dropped to less than 10 per cent of the total trout population.

Based on ongoing research, Parks Canada is confident they can rid the lake of all fish over the winter, and see the worm spreading the parasite die off in the next few years.

So far, Parks Canada has used gill nets and electro-fishing to catch 32,678 fish from Johnson Lake and its tributaries.

Hunt said only a handful of brook trout were caught last year, giving hope they will eliminate all fish from the lake over the winter.

“In terms of salmonids – the trout that are susceptible to whirling disease – I think there was less than a dozen fish last winter,” he said.

“I think we’ve been quite successful to date, but we always like to get a confirmation year where we just get nothing, as in zero, so we’re hoping we can get to that this winter.”

Partially draining Johnson Lake will make that effort easier.

Pipes have been laid at the eastern and western outlets of Johnson Lake to syphon water out, which is expected to lower the water levels by about two metres.

“There’s a lot of places along the margins of the lake, whether it’s logs or rocks near the shoreline that provide cover for the very small life stages of fish,” said Hunt.

“If we can get that water drained down, then I think it will increase our netting success and just provide less cover for those fish.”

Following the work at Johnson Lake, the long-term plan is to reintroduce native longnose suckers to replace the original ones mostly displaced by non-native trout.

The suckers won’t be restocked until it has been confirmed that the population of worms has died off.

“Within two to three years, or three or four years of having removed all the salmonids from the lake, we’ll have to go back in and test to make sure that’s happened,” said Hunt

Johnson Lake was closed to the public Oct. 1 and will remain off limits until mid-May 2020 while the work is completed.