BANFF – While much of southern Alberta is dealing with water shortages amid severe drought conditions, the Town of Banff has the fortune of drawing 100 per cent of its water supply from a deep underground aquifer.

The municipality has completed a study of the 60-metre deep aquifer, including forecast models on future water consumption based on resident population, growing visitation and climate change considerations, to meet conditions of a 10-year water licence application required by Parks Canada.

Town of Banff officials say all studies and data show the groundwater, which is drawn by three extraction wells, has been stable for 40-plus years and there is no danger of Banff experiencing a water shortage.

Michael Hay, the municipality’s manager of environment and sustainability, said three forecast scenarios were run based on low, medium and high resident population growth rates and increases in visitation.

“In all those scenarios, we did not observe any significant depletion in our groundwater aquifer, even all the way out to the 2040s,” said Hay.

The low scenario was based on 0.55 per cent residential population growth and one per cent increase in visitation, while the medium considered 1.1 per cent residential and two per cent visitor growth. The high scenario was based on a 1.65 per cent residential growth rate and three per cent visitor growth.

In addition, Hay said the municipality also ran a dry climate change scenario on the high forecast.

“We found that we didn't have any issues there either,” he said.

“There’s enough precipitation even in the driest climate scenarios that are currently being modelled to support the health of our groundwater aquifer, even if our demand grows dramatically.”

Most of Alberta is currently under moderate or severe drought conditions, including the Bow River, which is seeing some of the lowest water levels experienced in the past 24 years.

Due to a low snowpack in the mountains, the province is anticipated to face drought conditions into the summer, likely reaching a severity not witnessed since 2001.

Projected temperatures and precipitation patterns are jeopardizing water levels and escalating the threat of wildfires. There are currently 63 wildfires burning in Alberta, including carryovers from last year, and there are 51 water advisories province-wide.

Operating under a five-stage water shortage management plan, Alberta currently sits at Stage 4, meaning multiple areas are under water management. Stage 5 is a declaration of an emergency under the provincial Water Act, which has never been triggered.

The Town of Banff, a national park community, does not have a provincial water supply licence; however, Parks Canada has asked the municipality to formalize permission to withdraw water into a 10-year permit, as Fairmont Banff Springs and the Town of Jasper have been required to do.

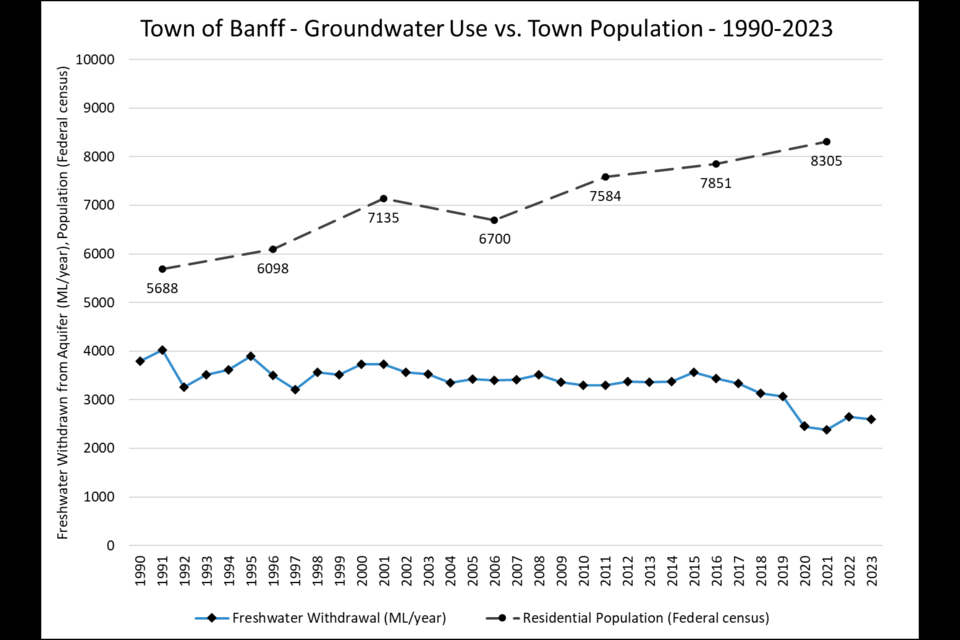

Data shows the community’s water consumption has been going down over the past two decades despite an increasing residential population, including a 5.8 per cent increase in population from 2016-21 to 8,300 residents, and exploding visitation to more than four million tourists.

The average annual community water consumption indicates 3.6 million cubic metres/year for 1990-1999, with the highest year at 4.0 million m3; 3.5 million m3/year in 2000-2009 with the highest year at 3.7 million m3; 3.3 million m3/year in 2010-2019 with the highest year at 3.6 million m3/year.

The average water consumption during the 2020-21 COVID-19 pandemic years was 2.4 million m3/year, when visitation plummeted. For 2022-23, the average annual community water consumption was 2.6 million m3/year.

“Our highest community water consumption was actually in the 1990s,” said Hay.

Hay said this is attributed to many different measures, including fewer system leaks due to infrastructure repairs and upgrades, and voluntary conservation measures following the introduction of universal water metering in 1997.

The use of more native plants that don’t require watering and fewer irrigated and landscaped yards as a result of increased housing density in town are also playing a role in the reduction in the community’s water use, he said.

Hay said residents and businesses have also tapped into the municipality’s environmental rebate program to make buying energy-efficient appliances like dishwashers, as well as low-flow shower heads and low-flush toilets more affordable.

“We really think that those rebates have raised the issue of water conservation to the forefront over the years,” said Hay.

“We’ve replaced over 1,000 toilets in our community from being very, very low efficient to now very high efficient toilets over a period of about 15 years, and in a community that has a population of 8,000, 1,000 toilets makes a big difference.”

Banff’s water supply is different from that of other downstream municipalities, like the City of Calgary which draws 60 per cent of its water supply from the Bow River with the other 40 per cent coming directly from the Elbow River via the Glenmore Reservoir.

Canmore’s drinking water does not come directly from the Bow River, but through a shallow groundwater aquifer that is hydrologically connected to the Bow River, and from the Rundle Forebay reservoir, which is primarily supplied by Spray Lakes in Kananaskis Country.

The Town of Canmore, which currently uses about 55 per cent of its licensed water supply and used almost three million cubic metres last year, is considered a small water licence holder in the province, accounting for 0.05 per cent of the provincial total of water licences.

Alberta water licences are administered under a “first-in-time, first-in-right” system in which older licences have a higher priority during water shortages. In the event of a water shortage, a “priority call” is made to ensure older licences receive water allocation before newer ones.

However, last week, major water sharing agreements were reached, with 38 of the largest and oldest water licensees in southern Alberta voluntarily agreeing to reduce water use if severe drought conditions continue to develop this spring or summer. These groups represent up to 90 per cent of the water allocated in the Bow and Oldman river basins and 70 per cent in the Red Deer basin.

Shannon Woods, water resource engineer for the Town of Canmore, said the municipality has not been mandated to take less water.

“But the province is saying please be mindful, please plan, be prepared, and if you wish to put in restrictions now, give-er,” she said.

The Town of Canmore is in the process of developing a drought response plan, but already had plans over the short- and long-term to manage water use, including ongoing work to detect and repair leaks.

Replacing aging water mains is on the to-do list as is installing flow meters in major water mains to help detect leaks.

“For example, there was a building that had leaks that wasted 6,000 cubic metres within two months,” said Woods. “This is enough to fill three Olympic swimming pools.”

Canmore is also developing a water restriction plan, which will include a webpage for public information, internal monitoring to inform different water restriction phases, and the potential for additional restrictions in the event an emergency is declared under the water act.

Outdoor water restrictions will be outlined for each of the four different stages, although there will be some exceptions that could include occupational health and safety needs, such as allowing for washing outdoor surfaces at kindergartens or daycares, or for dog kennels.

Woods said consumptive water use will be targeted, meaning water that is not being returned to the Bow River within a matter of hours or days.

“When I water my lawn it is not returning to the Bow River in any expedient terms, but when I flush the toilet it will get there within days,” she said.

“That’s the difference between consumptive and non-consumptive use, so consumptive we’re targeting that to keep the flow of the Bow River up for our neighbours downstream.”

Once the plan is finalized and approved, Woods said it is anticipated that Canmore will move into stages of water restrictions at some point this year, perhaps preemptively even if there is sufficient water.

“If we continue onto what’s anticipated to be a very dry, very hot year if it follows kind of 2023 seasonal conditions – just even if the province doesn’t call for us to make any reductions – I think it’s the smart and environmentally conscious thing to do,” she said.

The Town of Canmore continues to monitor groundwater and reservoir levels, with Spray Lakes Reservoir about 13 per cent full as of mid-April, which is trending similar to this time last year.

“Between June and July timeframe, that is where you see the majority of your snowpack melt,” said Woods.

“Last year with the low snowpack, the Spray Lakes did not see that typical cortile shift upwards, so it trended low due to the low snowpack last year."

Close to the headwaters of the Bow River, both the municipalities of Banff and Canmore say water conservation is vitally important.

“We don’t want to get complacent and feel like our water supply is never ending,” said Hay.

“If we save water in Banff, you’re helping people downstream, maybe not this year, but over time, over many years as that water moves through the system,” he said, noting 90 per cent of the water pulled from the deep aquifer goes into the Bow River after being used and cleaned.

Woods said there are many neighbours downstream in the Bow River water basin, such as Calgary.

“We are relatively close to the headwaters of the Bow so as environmental stewards, it’s very important to watch what we do as it affects everybody else downstream,” she said.

Alberta Environment is recording some of the lowest water levels in the Bow River for this time of year in the last 24 years.

Canmore Coun. Wade Graham, who regularly floats the Bow River, said he recently had to walk his boat several times.

“It was alarming,” he said.

“It was the lowest I’ve ever floated down the river and we did have to walk our watercraft several times.”