BANFF – It started with a train derailment.

That is how the story of how Banff Indian Days began in 1894, a topic Stoney Nakoda First Nation elder Roland Rollinmud spoke about during his lecture at the annual Chiniki Lecture series earlier this year.

“Banff had a derailment of a train and the tourists were stranded,” he explained. “The Stoneys were camped so the [train conductor] went to the camp and asked if they could help him entertain the tourists.

“And of course they were doing their harvesting and the [conductor] said he would do an honorarium – give them some food or money, so that’s where it all began.”

Reflecting on the past 130 years of what started with a derailment that grew to an annual tourist attraction until the three-decade and a half hiatus in the 1970s, the speakers at the event took an honest look into Banff Indian Days.

“[Banff] wanted to create an elite mountain town ... with no acknowledgement of how it would impact the Nakoda people,” said Thompson Rivers University associate professor Courtney Mason.

Working as a research chair with rural livelihoods and sustainable communities, Mason discussed how the exclusion of Stoney Nakoda people from their traditional lands was problematic and “sinister.”

“There was legislation created to target Indigenous practices [such as] the Sundance and sweat lodge ceremonies. There was a lot of confusion about what the government thought these practices were and how they were threats to Christianity and the new way of life they imagined for indigenous people,” Mason said.

When Europeans immigrated to Canada and a new government was formed, new rules and laws were implemented onto Indigenous peoples, including the requirement to live on a reservation forcing bands to abandon their migratory lifestyles and send their children to residential schools, developed to assimilate the children into Euro-Canadian culture.

But despite the government’s aversion to traditional cultural Indigenous practices, after the train derailment in Banff, a tourism opportunity was discovered.

“There are a lot of complex histories there that need to be explored,” Mason said.

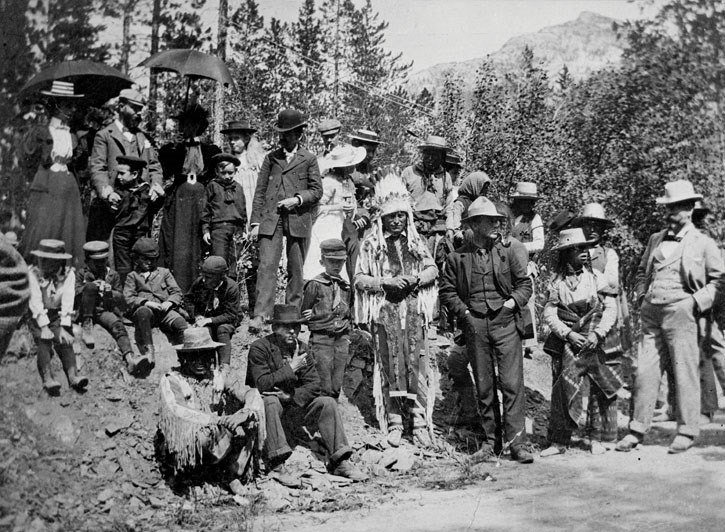

“I’m really fascinated in the roles Indigenous people played in promotion for Banff as a tourist site ... there is lots of imagery available and most of that imagery has been analyzed very simplistically in the sense that this painting or this picture presented stereotypical representations of Stoney Nakoda people.

“In my mind, without talking to local people and understanding the context that is a very simplistic reading.”

Indian Days was held from the 1880s until 1978, when Stoney Nakoda people were “welcomed” back to the park for a couple of days out of the year. They were allowed to celebrate their traditional cultural practices under strict guidelines, while also expected to open their teepees and pose with tourists.

But despite all of this, the Stoney Nakoda used their time as a way to challenge stereotypes, colonialism and assimilation, according to a former Chiniki Lecture speaker Jonathan Clapperton, with some chiefs even reversing the stereotypes.

“I know I might not understand what ‘civilization’ means. It’s your language, but I still think lots of times that you white savages do not know nothing about your word, the meaning of civilization,” Clapperton quoted Chief Walking Buffalo as telling one visitor to the grounds.

The annual event was discontinued in the 1970s and took a more than three-decade hiatus before elder Rollinmud began researching the history and how to revive Indian Days as something more meaningful than how it began.

“When I was 14 standing outside the tent, my grandmother told me to make sure we never lose this because if we do then we lost who we are – I didn’t know what she meant at the time, but it stayed with me,” Rollinmud said.

After becoming an artist and studying at the Banff School of Fine Arts, Rollinmud said he was sitting outside when someone suggested the Stoney Nakoda artist should paint Indigenous history.

“That’s when the words of my grandmother came back to me ... [Banff] was very important to the Stoney Nation, so I was inspired after that,” he said.

Rollinmud began putting out feelers for who might want to help get the event rolling again when he stumbled across two Australians who were interested, which led to conversations with Parks and three years later Indian Days was reintroduced as a cultural celebration in 2005.

“We need to get the youth involved more in understanding our way of survival during this time. So today all the things that seem to be hard, at that time we were thinking of how to get food for the winter when this time is very simple and you can go to McDonald’s to get whatever you want,” he said with a laugh.

Now, since the reintroduction 14 years ago, Banff Indians Days is a place where different cultures can come together and learn.

“There is so much more to the First Nations – we are the spirits to Canada,” Rollinmud said. “We are just waiting to be asked what you want to learn of Canada and that’s the importance of who we really are because Canada is really the most beautiful place.

“I want to say I am proud of what I did and if I can do it, you can do it too ... now I have 22 grandkids to teach.”