A sardine-sized fish that thrived in the warm Cambrian seas 505 million years ago has given researchers a new understanding of the evolution of vertebrates.

The fossil beds found in Yoho and Kootenay National Parks, with their remarkably preserved fossils, provided this discovery as paleontologists Simon Conway Morris of the University of Cambridge and Jean-Bernard Caron of the Royal Ontario Museum studied a specimen fish known as Metaspriggina walcotti, now recognized as one of the first vertebrates.

Metaspriggina also shows features – arch-like structures near its head – that provide the first clear evidence, the first of its kind in the fossil record, of where evolution of the jaw began. Until now, that structure was purely hypothetical, according to Conway Morris.

“If you go to review articles in scientific literature, they will have an illustration of a hypothetical ancestor,” he said on Tuesday (June 17).

In this hypothetical ancestor, as it is with all fish, the gills are located on the sides of the fish just behind the head along what is known as the branchial chamber. A fish sucks in water through its mouth, it passes through the gills where oxygen is extracted and carbon dioxide is released. This gill area, Conway Morris said, is supported by a series of rods also known as branchial arches.

“What is very intriguing, going back to this hypothetical ancestor, is everybody said this is what the ancestor ought to look like. You have a row of effectively identical gill arches and on first examination that is exactly what Metaspriggina shows. In other words, it shows what everyone in principle thought should be the ancestor. They are not figments of our imagination, but hypotheses and when something literally swims into view and says ‘here I am,’ that is encouraging.

“There’s an enormous amount of interest in how jaws evolved. Because once they did, literally a whole new world opens up for the vertebrates because you can chew, grasp, grind, crunch, nibble …”

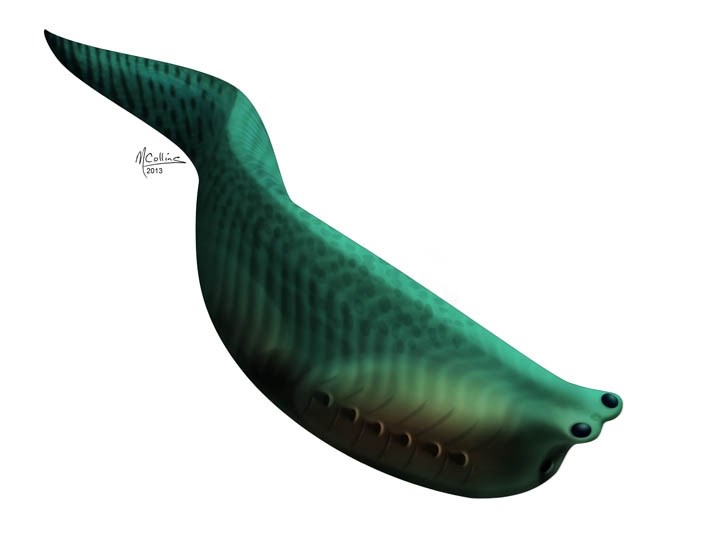

Metaspriggina, however, did not have a jaw per se, rather a set of branchial arches closest to its head are slightly thicker than the other arches and are not connected to gills.

“There’s this difference and because we have good reason to think that ultimately, much, much later in geological history, that became the jaws, it … provokes my thinking in what this animal shows,” Conway Morris said.

“I’m just wondering if, and this is pure hypothesis, from (Metaspriggina’s) general shape and the fact it doesn’t have jaws, we think it fed on small food particles. Suppose it was able to swallow a larger prey, which would of course provide more nutrients?” Conway Morris asked. “Just supposing, this anterior most set of gill bars assisted in that process, grasping larger food; we’re on the very, very first step of a very, very long journey from originally having gill bars to what becomes a functioning jaw.”

In this “hypothetical ancestor,” Conway Morris said the gill bars or brancial arches are always shown as a single unit, not divided into an upper and lower set, which is what Metaspriggina in fact shows: the forward-most brachioal arch has a lower and an upper arch.

“If you want to make a jaw, basically you’ve got to break each one so that it can ultimately form into an upper jaw and a lower jaw and it will swing, of course, on a hinge and you’ll have lots of muscles developing to allow it to move. In our Metaspriggina, unlike the hypothetical ancestor, we see that these gill bars are already forming two sets not a single set.”

The bars closest to the head do not have any gills attached them and, in fact, are slightly thicker than the rest, “and this subtle distinction may be the very first step in an evolutionary transformation that in due course led to the appearance of the jaw.

“There’s this difference and because we have good reason to think that ultimately, much, much later in geological history, they became the jaws. It provokes my thinking in what this animal shows.”

Metaspriggina has a small, circular opening for a mouth, large eyes that suggest good visual acuity and a musculature that tells Conway Morris and Caron that it swam, just like a trout or a salmon, in a sinusoidal or a sinuous back-and-forth motion. And with big eyes and the way it swam, like a modern fish, tells Conway Morris that, “This must have been a very agile creature and it probably swam at a reasonable rate, so this, in a sense, is a fish in a hurry.”

Otherwise, without fins – which would eventually evolve into legs in one group – including on its tail, it is obviously a primitive fish.

“If you saw it darting through the water, you’d say there goes a fish. When you’ve got it in the lab you’d say well, yes. They’re a very primitive fish.”

But it would not surprise Conway Morris if fossils were found that showed Metaspriggina did indeed have fins.

“That is the other key observation. It is perfectly possible that more material will come back to the Royal Ontario Museum, there may be other structures that we’ll see and quite often in this game you go back to your original material and you suddenly realize that something that is just visible. You hadn’t really overlooked it, but you can’t be sure because as fabulous as this preservation is, there isn’t so much something that you overlooked as you can’t be sure.”

Aside from being one of the earliest vertebrates on Earth and the first to display that starting point in jaw evolution, Metaspriggina is, as Conway Morris pointed out, “one stepping stone in an area where we already have a number of stepping stones.”

“We like Metaspriggina because it hints at so many things. It is rich in hypothesis and that is really where the importance of the story lies.”