CANMORE – The first trailer for The Last of Us television series, partly filmed in the Bow Valley, was released this week.

While the show is new, the history of filmmaking in the Bow Valley goes back over a century.

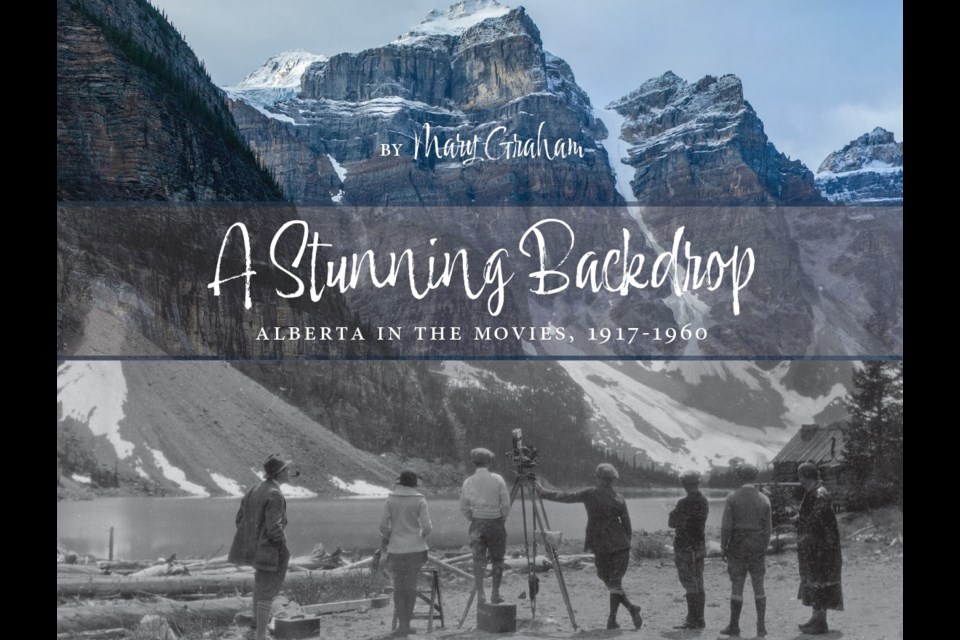

In her new book, A Stunning Backdrop: Alberta in the Movies: 1917 -1960, Mary Graham explores that history, as well as how the Îyârhe (Stoney) Nakoda used early films to preserve their culture and practice rituals that were banned at the time.

“A lot of the early directors were sympathetic to what was going on with the Indigenous populations and the Nakoda were very proactive and they knew what they were doing, and they formed relationships with the directors,” Graham said. “They aligned themselves with powerful people who could help them. That is probably one of the biggest things that preserved their culture for them. They were very proactive.”

Graham spent more than a decade researching the story of film in Alberta, including working with Îyârhe Nakoda elders to identify the Îyârhe Nakoda captured on film decades ago.

It all began when she was living in Kauai, Hawaii with her family and they were visiting movie locations on the island using the book The Kauai Movie Book.

“I thought, there must be something in Alberta and when I got back, I couldn’t find anything,” Graham said. “I got the idea of doing a landscape book, a coffee table book.”

She would meet with the film commission in Calgary, who referred her to the Film Commissioner of Alberta.

“We met a couple times and nailed down a concept and I started researching,” Graham said. “I kept finding more films in the research I did and started to discover that the filmmakers who came here were important to early filmmaking, and I thought there is something more to this and there always was.”

Once she was three years into the process, she realized she had to split it into two books. The original manuscript was 1,000 pages, but she was able to get that down to 250 pages.

Alberta in the early days of film, as movies moved off the studio and into actual locations, was seen as a location untouched by civilization.

“Alberta was seen as the far country, God’s country, the last uncivilized outpost on the continent,” Graham said. “It was because of the Rocky Mountains, which were prevalent in literature at the time. People were always awestruck with Alberta and Banff.”

At the same time, the CPR tourism government campaigns were promoting the Rocky Mountains.

“They would bring up journalists and Banff was very desired as a place to go,” Graham said. “One thing they loved was the light, and even then, they noticed it was cinematic.”

A genre developed around Alberta at the time in the film industry, and film crews would often travel into the mountains to get stunning shots for their films.

“They would pile their lights and their film and screens into the back of a vehicle and go out on location,” Graham said. “Alberta was a primary destination for that.”

Amid those stunning shots, the Îyârhe Nakoda could be seen on film, living their traditional life even as the government was pushing them to change. One film Graham cites was the Frank Borzage 1922 film The Valley of the Silent Men, which portrayed the Îyârhe Nakoda living their traditional life on film.

“There was a little boy named Frank Powder Face and his family and their teepee. The Mounties approach the teepee and Chief John Hunter comes out and little Frank Powder Face is at the front of the teepee and his mother is tanning hide on a traditional structure,” Graham said. “It is in a very natural setting.”

As for why the Bow Valley was a frequent place for film and vacations by those in Hollywood, from Mary Pickford to Marilyn Monroe, Graham said it came down to the connections created in the Bow Valley.

“There was a huge connection with the directors and movie stars,” Graham said. “Banff and Canmore, they are very different mountain communities. It is an iconic location. It is very well known. I was just in the Oscars Archives, and they were just crushing on Alberta.”

Her book covers to 1960, the year that changes were made by Parks Canada and the preservation of the Parks took centerstage over filmmaking.

“They weren’t was welcome, and filmmaking all but stopped.”

The book, published by Bighorn Books, will release on Oct. 31.