There are inherent dangers in the Canadian Rocky Mountains that exist in few places in the world.

You're unlikely to encounter a bear or cougar in Toronto or Vancouver, but in mountain communities carrying bear spray is second nature for many people.

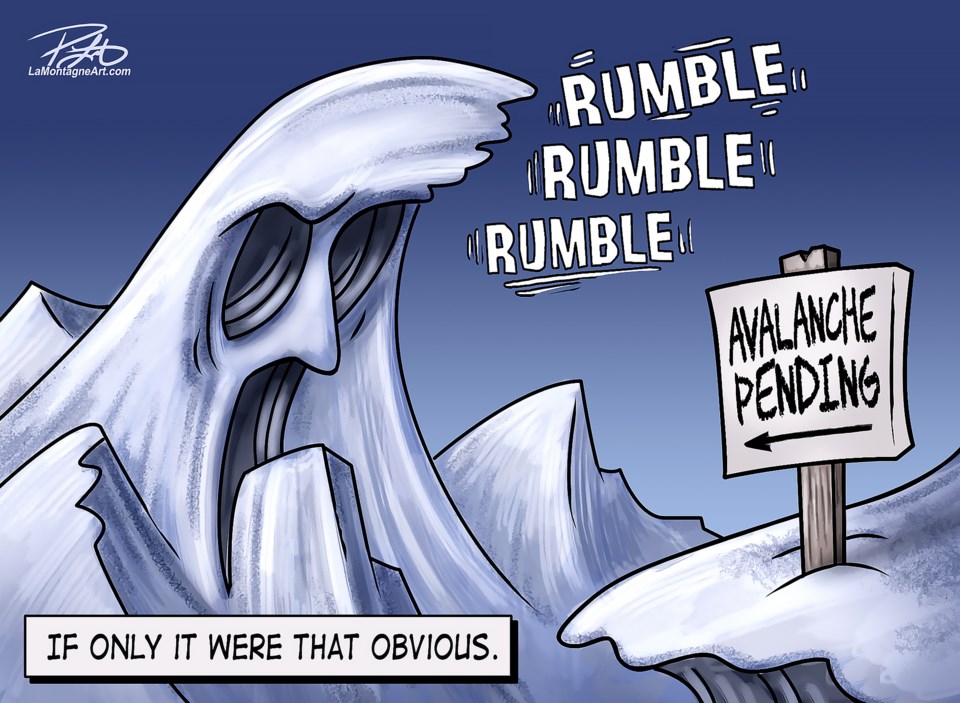

For people who live or visit the mountains in the winter, the threat of avalanches is a real issue for those travelling into certain areas across the Rocky Mountains.

This winter has seen several avalanche-related fatalities in what is one of the more deadly years in recent memory.

Since January, there have been six avalanches that have led to 15 fatalities and six injuries.

That’s a dramatic increase from six avalanche-related deaths in the 2021-22 winter season, nine in the winter of 2020-21 and eight in the 2019-20 winter season. It’s on tap to be the most deadly avalanche season since 2002-03 when 29 people were killed in 14 avalanches.

There have been other avalanches such as one on March 5 east of Pemberton in which two people were buried. Fortunately, additional deaths were avoided, but the risk remains a possibility.

Certain avalanches will stand the test of time. In 2003, an avalanche in British Columbia killed seven people from a school group. Another nine people died and 25 were injured in a 1999 avalanche in an Inuit village in northern Quebec, and eight snowmobilers were killed southeast of Fernie, B.C. in a 2008 avalanche. In 1910, an avalanche near Rogers Pass outside of Revelstoke left 62 people dead.

But while certain avalanches will always get more notoriety than others, each one leaves an indelible mark on those who survive them, those who knew people involved or those who were involved in the aftermath.

As much as it is easy to fall back on statistics, each number represents a life that can no longer add to the moments and memories.

While Alberta has avoided any fatal avalanches this season, with all deadly avalanches taking place in British Columbia, the mountains are equally dangerous regardless of which side of the border they’re on.

In 2021, the Outlook produced a four-part series Buried in the Aftermath analyzing individual avalanche incidents involving the guiding community, the responses to fatalities from avalanches, the work being done in the guiding community and how people cope following a tragic incident.

It was clear through the series that significant mitigation and education has been completed, but that there was still room to improve.

Avalanche safety and the resources for it have increased over the decades. An influx of $25 million to Avalanche Canada from the federal government for a one-time endowment showed the priority of continuing to improve safety and education when it came to the threat of avalanches.

Conditions can be unpredictable, but at no other time have there been more resources available for people to access to better inform decisions before heading into avalanche areas. Other specialized units such as Kananaskis Mountain Rescue, local search and rescue units in mountain communities and Parks Canada visitor safety specialists are among the most trained in the world.

Those resources have been invaluable, but should never be looked at as a finish line but rather a starting point for allocating resources.

As the Alberta government has prioritized tourism as an economic driver, with areas such as Kananaskis Country and Banff National Park only showing signs of more winter tourism, a greater priority in resources needs to be allocated to assist in education, prevention and rescues when it comes to avalanches.