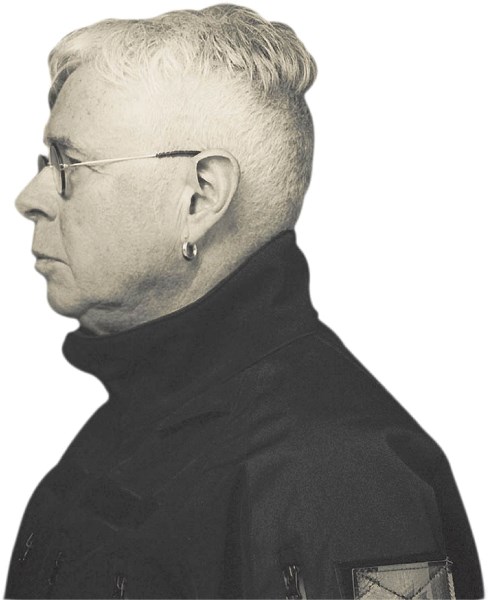

Bruce Cockburn.

Really, unless you’ve been living in a cave for the past four decades and are somehow unaware of his storied life, this story could end now.

In the newspaper business, though, white space doesn’t sit well with the industry, so…

Bruce Cockburn, one of Canada’s most-loved musicians, and likely the only one whose celebrity status is unconventionally closely tied to a weapon (rocket launcher, of course), will fittingly close out the Canmore Folk Music Festival, solo, just he and a guitar, on Monday (Aug. 6).

In a nutshell, Cockburn’s career has now spanned 40 years, his awards would fill a tractor-trailer and he’s been recognized far and wide, and farther still, for his humanitarian work around the globe.

In reading over his bio, which runs pages, one might suspect a carefully planned thread ran through it all; possibly with a well thought out end result in mind.

For those who have trouble balancing their chequebook or knowing what next week might bring, you may find it comforting to know that Cockburn admits he’s never really had a plan.

“I don’t really think of it as a career,” he said during a phone interview from San Francisco last week. “I think this is what I would have been doing anyway. I dropped out of music school in 1966 and joined a band in Ottawa. From 1969 to 1970 is really when I got established.”

Juno Awards followed quickly, as he was named Canadian Folksinger of the Year from 1971 to ’73.

“It’s been long and winding and interesting – and as far as I know, it’s going to keep going. Forty years ago I had no plan, any more than I do now. I just do the next thing that comes along.

“But I was lucky in that I met up with Bernie Finkelstein as a manager. He’s a gifted strategist who always knows what’s coming up around the corner. It’s been a good symbiosis.”

For musicians out there, just like Cockburn hasn’t really had a career plan to follow, at times he also has to blow the cobwebs off one of his songs from back in the day.

In fact, he admitted that sometimes, when he wants to shake up a set list, he has to go back and re-learn some of his own material.

Now, the idea of re-learning one’s own material might seem odd – to those in an up and coming band who are still embracing bar gigs while holding down a day job.

But consider… the now 67-year-old recently released his 31st album, Small Source of Comfort, has won 12 Juno Awards, been nominated for 31, holds a number of honourary doctorates, is a member of the Order of Canada, has radio, TV and film credits… the list goes on.

Small Source of Comfort is a collection of songs of romance, protest and spiritual discovery. Many of the new songs come from his travels and spending time in places ranging San Francisco to Brooklyn to the Canadian Forces base in Kandahar, Afghanistan.

“Each One Lost” and “Comets of Kandahar,” one of five instrumentals on the album, stem from a trip Cockburn made to Afghanistan in 2009. “Each One Lost” was written after Cockburn witnessed a ceremony honouring two young Canadian Forces soldiers who had been killed that day and whose coffins were being flown back to Canada. It was, remembers Cockburn, “one of the saddest and most moving scenes I’ve been privileged to witness.”

“Called Me Back” is a comic reflection on the frustrations of waiting for a return phone call that never comes. Then there is “Call Me Rose,” written from the point of view of disgraced former U.S. president Richard Nixon, who receives a chance at redemption after being reincarnated as a single mother living in a housing project with two children.

And though he has a new album out, Cockburn said he doesn’t really look at his solo touring this year as being in support of the album. “I never think of touring as in support of an album,” he said. “To me, it’s touring for people, which is a totally different thing. I enjoy working in the studio, but I prefer the live option.”

At this point in his life, Cockburn is managing to look both forward and back. On the one hand, the documentary Pacing the Cage is out; an intimate look at his life, music, family and religious beliefs. On the other hand, he’s looking forward to whatever challenge next presents itself. Presently, he has a new baby in the fold and is working on the possibilities of touring with a youngster in tow.

“I’m gigging in England for two or three weeks this summer and the baby may be part of that. But my partner has a regular job to attend to and we’re not in a position to hire a staffer like Angelina Jolie.”

As to past and future, “I’m looking more forward than back, though,” he said. “I look back in the sense of the older songs that make up a good part of the show, but in looking forward I don’t generally know where that is, I’m waiting for a direction to suggest itself.”

In looking back, Cockburn said he does sometimes wonder if he made the correct career move in staying in Canada.

“Everybody has regrets in their life, but in general, I think I’m where I’m supposed to be and I’m satisfied with where I am. In 1970, though, I started to tour further afield and people I knew were going to the states, Joni Mitchell, Neil Young, and there was a certain pressure to do that, but I resisted.

“I thought you should get established in your own country first and then move on. It hasn’t taken anything away from other Canadians, but it might have changed the shape of my music career.”

Finally, of course, Cockburn may be as well known for his humanitarian work as his music.

Again, in keeping with a no-plan plan, Cockburn said his humanitarian efforts, travelling to war-torn and impoverished countries, for example, “just come up when they do.” Humanitarian work has taken on a life of its own during his life.

“My parents encouraged me to pay attention to the news, and they always had an attitude to charity. Rich and poor, I grew up with that understanding and there was a sense of sympathy for people being uncomfortable.

“And in the ’70s, I started paying more attention to people. It was a change in attitude, I was pretty solitary before that, and I became more interested in what was going on around me.

“I became interested in Central America, talked with a girl from El Salvador and started reading the poetry of a Jesuit minister. He was amazing and I thought, ‘wow, if this is what the revolution is about…’ I also had an invitation from Oxfam to travel in Central America.

“But I also travelled more in Canada and met a lot of aboriginal people. I heard their stories and thought, ‘this shouldn’t be happening in this country.’”

In helping out charities and humanitarian groups, he said, “they need people with skills. I don’t have those skills, but sometimes they need someone with a reputation and that can be where I come in.”

Cockburn continues his travels. During a more recent trip to Bolivia, where his daughter is doing PhD research in a mountain village, he said still, as someone from outside the Third World, “you notice that huge disparity between their world and ours.”