On March 11, 2019, an avalanche plummeted down the side of Mount Stephen in Yoho National Park, travelling from the bowl at the top of the mountain to the base of a popular ice climbing route on Massey’s Waterfall below.

It landed on six people – two guides and four participants – on a multi-day ice climbing camp hosted by Sarah Hueniken Guiding. Two of the clients were buried in the slide, one lost her life – Sonja Findlater – and the other was able to walk away physically unharmed, but has had to reckon with the post-traumatic stress of the near-death experience and questions about the process that dealt with the aftermath of this avalanche.

The first question Michelle Kloet remembers asking after being buried in the avalanche was what the mountain guide had yelled before snow started falling from above her head.

“All of a sudden, I hear a scream – I hear a word, but I don’t know what it is,” she said. “We jumped to the wall and the next thing I know, the snow is falling down on us.

“I had no concept of what this was … it started coming down harder, and harder, and harder. It intensified. I remember thinking, ‘Oh my goodness, we are going to be buried from the feet up.’ ”

Kloet was standing at the waterfall, but shifted the position of her head slightly.

That is when she recalls being pulled backwards by her helmet from the avalanche and realized what was happening.

Unable to move a muscle after the avalanche came to a stop and she was buried, fear and uncertainty gripping every ounce of her spirit – Kloet thought the word was “avalanche,” but as it turns out, the guide was trying to say “everyone to the wall.” Only half of the first word made it out when the worst-case scenario ice climbers and guides train for occurred.

“It was awful, it was probably one of the most awful things that has happened to me,” she said.

“The sad thing is that what happened to me was not the worst day of my life. I have had worse days in my life, but the aftermath of Massey’s has shaken me. It has shaken my ability to trust.”

Ice climbing has been increasing in popularity as an outdoor pursuit in the past several years and the 10 women who signed up for the advanced camp were eager and excited to learn new skills. The first day of the camp had been spent at Haffner Creek, but the next day the group split up to pursue different objectives. It was also the first day of daylight savings time.

Massey’s has become almost mythical in its aftermath for the effect it had on the guiding and ice climbing community. In addition to the trauma experienced by Kloet, the guides have suffered immensely from the loss of a dear friend, and spent the past two years focused on healing from their worst imagined nightmare come to life.

"Powder cloud on Mt. Stephen, indicating an avalanche of some size"

The guides have spoken to the media for the first time since the avalanche in an interview with the Outlook about how this incident has affected them.

Merrie-Beth Board and Benjamin Paradis, independent guides hired by the guiding company to assist with the camp, were with the group at the waterfall. Hueniken was with another group at Guiness Gully. A third guide was leading a group at Carlsberg Column. Hueniken, her partner Will Gadd, Board and Paradis agreed to be interviewed if questions on the day of the avalanche were referred to their guides' report for concerns of being re-traumatized.

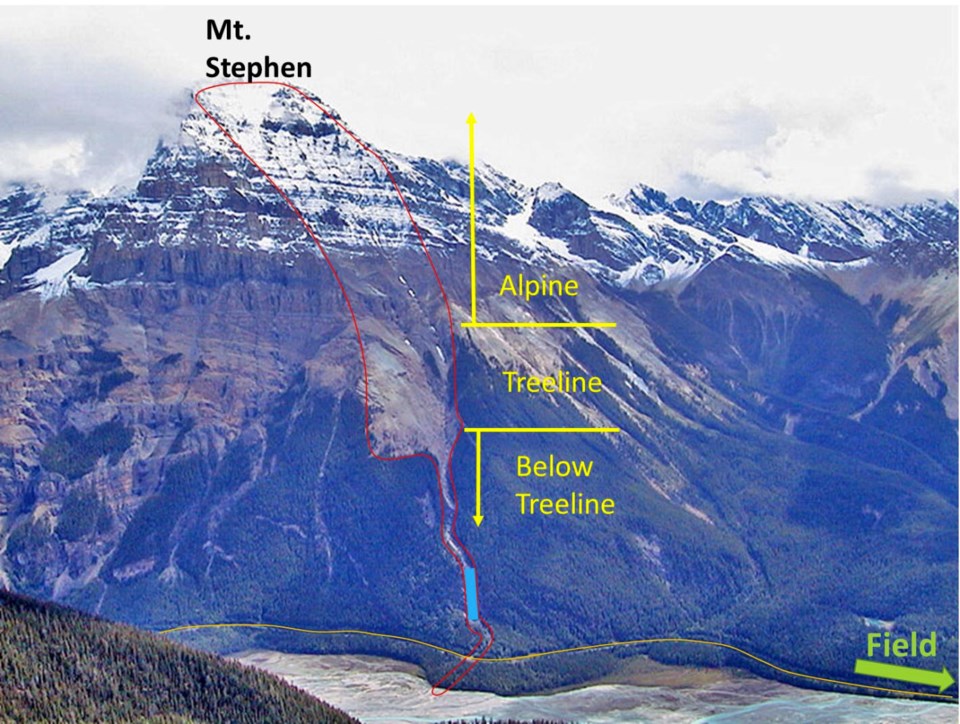

Hueniken was with two participants crossing the railway tracks in nearby Field, B.C., at 2:27 p.m. when “one participant noticed a powder cloud on Mt Stephen, indicating an avalanche of some size,” according to the guides' report. The report from Alpine Solutions later estimated the avalanche began in the bottom half of the alpine zone and above the treeline.

The blue square shows the estimated area where the avalanche began at Massey's on March 11, 2019, according to the Alpine Solutions report. Handout

The blue square shows the estimated area where the avalanche began at Massey's on March 11, 2019, according to the Alpine Solutions report. HandoutBoard tried to call out to her group to get as close to the waterfall as they could, but the snow was already on top of them.

Findlater and Kloet were swept away and buried – Findlater under 1.8 metres of snow and Kloet with her head and arm partially out of the avalanche debris.

Hueniken immediately raised the alarm with Parks Canada’s visitor safety specialist team and headed for the scene. Findlater wasn’t just a participant in the camp, she was also the camp manager for more than a decade and a close friend of Hueniken’s.

The loss has gutted the experienced guide and climber, and even today speaking about what happened is difficult for those who were affected by its aftermath. Hueniken said the incident lives with her every single day, every hour and sometimes every minute – it will always be a part of her and nothing can prepare a guide for something like this.

“I am in the process of re-learning how to live, that is the honest truth,” she said. “There is nothing easy about this path and it is not linear. It took me nine months just to be able to go to the grocery store. I was and can still be suddenly anxious about everything and everyone and locked in a circle of self-doubt, shame and despair. Not until I spoke with many other guides who experienced similar tragedies, did I start to resurface.”

She has helped co-found the Mountain Muskox peer-mentorship program for those who experience trauma in the mountains. The goal is to provide a safe space for both professionals and recreational backcountry users who are grieving from loss and the effects of a traumatic experience. Hueniken said the support group doesn’t discuss the difficult events they experienced, but focuses on relating to each other’s struggles.

“I am still finding my path,” she said. “I guide much less and avoid most avalanche terrain, knowing that I could never live through another tragedy. I ask myself every day, how can I possibly make Sonja proud of this life that I am fortunate to still live and I work really hard at trying to not keep living in the regret of that day. Some days I can, and some days I can’t.”

It is important for Hueniken that her friend’s memory and legacy in life is honoured and not forgotten.

Described by many as an incredible ray of sunshine lighting up any room she entered, Findlater’s death was felt deeply by her husband, parents, sisters, nieces and nephews, and friends. After the avalanche, when Findlater was in hospital and her family was with her, Hueniken and Gadd were by their sides.

They have remained close and together honour her memory and grieve her loss.

"Sonja was one of my dearest friends and who I started these camps with – 15 years of friendship," said Hueniken. "She was a soul that inspired the best out of people and was the most genuinely caring and giving person I know."

They have been advocating for change to how the industry, and the Association of Canadian Mountain Guides (ACMG), handle critical incidents in the backcountry involving guided groups.

Guides, survivors of avalanches support ACMG's post-critical incident response review

As a result of what Sheila Churchill and her group experienced in 2016 when her husband Doug was buried and died as a result of his injuries, the ACMG has undertaken an extensive review of its post-critical incidents.

It has hired Alpine Specialists to conduct a post-critical incident process review with recommendations.

In the aftermath of Massey’s, Hueniken and another guide who was part of the camp that day, have pushed for this review as well.

Hueniken said she believes the issue is not one of guides versus clients, but one where all parties want the same changes, which could have given those involved in this particular avalanche fatality direction and a path “when there was none for us at the time.”

“I gave all my suggestions and experience to them in very lengthy discussions and interviews, and I trust that they will take all of the learnings they have accumulated from both a guide and client perspective into a well thought out report,” she said.

Learning from these types of events, especially when they have a low probability and high consequence, is critical for a self-regulating industry to demonstrate transparency and accountability.

It is something Kloet would like to see occur as well. She has publicly questioned what happened that day and the aftermath of what was a life-changing traumatic experience for her. She has three specific areas of concern: the communication of risk to participants; the amount of time the group spent in complex avalanche terrain practicing skills and techniques; and that the group’s backpacks, which contained avalanche rescue gear like shovels and probes, were unsecured and swept away.

While the group was on an ice climb located in what the avalanche terrain exposure scale defines as complex, the historic information with respect to avalanches reaching the waterfall below showed it was a low probability event. According to the guides' report, all members of the team helped assess the risk that day and did not identify or forecast this type of avalanche as being likely.

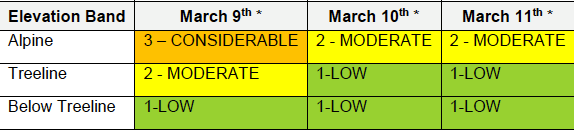

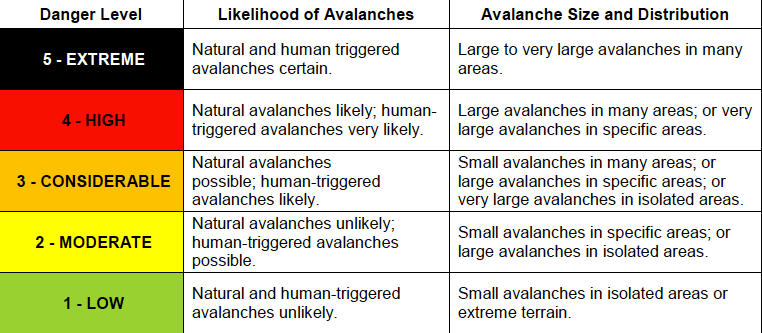

The Parks Canada public avalanche bulletin from that day had the risk of avalanche as moderate from the alpine level and low for the treeline and below treeline, according to the report by Alpine Solutions. The North American avalanche danger scale, shown in the Alpine Solutions report, lists the five levels of risk as low, moderate, considerable, high and extreme.

The Parks Canada public bulletin avalanche danger from the Alpine Solutions report.Handout

The Parks Canada public bulletin avalanche danger from the Alpine Solutions report.HandoutThe investigation into the slide revealed that high elevation winds had affected the snow in the bowl at the top of the mountain.

The winds were not felt at the valley bottom overnight, but they had loaded a windslab above that may have been triggered by a cornice fall, or reaching a threshold from the effects of the wind.

Avalanche rescue equipment buried in avalanche

Even though she had her AST1 training and avalanche gear with her heading into the waterfall, Kloet said when the group didn’t practice using it, she put the potential for a slide out of her mind. Nobody involved with planning the climbing camp expected this type of avalanche to occur.

“I made the incorrect assumption that we were not in avalanche danger, or it was very low,” she said.

The North American avalanche danger scale from the Alpine Solutions report. Handout

The North American avalanche danger scale from the Alpine Solutions report. HandoutThe CR1901 ACMG complaint report noted there were "several testimonials" from guides and guests that discussion of the "terrain and hazard were covered on more than one occasion.

Once beneath the frozen waterfall, they put their backpacks, with the avalanche rescue gear inside, in an ice cave while they climbed. While complex terrain, Massey’s is well-suited to teaching ice climbing techniques as the first pitch is quite challenging, but the second is much easier.

It means guides can lead climbers up the first part, then coach them as they practice leading on the second pitch.

That is exactly what Board and Paradis did that day. On the second pitch, two participants were able to practice leading a climb using pre-placed ice screws. They began climbing at first light and had returned to the base of the waterfall at 2:10 p.m. One of the participants had asked for a demonstration of a V-thread – when two holes are drilled into the ice to form a V shape and rope is threaded through to create an anchor point. Paradis was demonstrating the technique at the ice wall; Findlater was a few metres away removing her equipment; Board was near the waterfall when her phone rang to warn her at 2:27 p.m. The backpacks, Findlater and Kloet were swept away. Kloet’s previous avalanche rescue training kicked in and she began to swim, praying she didn’t hit a rock or a tree. In her mind she went through what to expect.

The mass of snow would slow first, before stopping, and she needed to get a limb out in the air, and clear a space in front of her face for an air pocket.

“I managed to get my left hand out of the snow,” she said. “I had my right hand in front of my mouth and I took a deep breath. I was in concrete – I could not move a millimetre.” She could wiggle her hand in the air and could still see the sky, so she had an airway. But Kloet had no idea at this point where the other members of her group were. She was concerned a second avalanche could come down on them and they were still in danger.

According to the Alpine Solutions report, the general avalanche path is in red, while Massey's ice climb is in blue. The alpine area, the treeline and below the treeline are also shown in yellow. Handout

According to the Alpine Solutions report, the general avalanche path is in red, while Massey's ice climb is in blue. The alpine area, the treeline and below the treeline are also shown in yellow. HandoutOne of the guides found her and was able to clear the snow away to her chest, according to the guides' report. But at that point it was becoming clear that she was not the only one buried. She used her cellphone to call for help.

Findlater was located underneath the avalanche debris and in that kind of scenario, every moment is critical. The two guides and two climbers not caught in the side began using improvised tools, like their helmets, crampons, sticks and hands to dig one metre down. Hueniken arrived with shovels 20 minutes after the avalanche and once Findlater was free of the snow approximately 10 minutes later, they began CPR. Alpine Helicopters Inc. responded to support the public safety specialists who had arrived and STARS air ambulance was also dispatched to Field.

Kloet returned to the hostel. It was not safe for anyone who wasn’t involved in the rescue efforts to remain, as there was still the risk of another slide. She had only bumps and bruises, but no hypothermia from being in the snow for 50 minutes before being freed.

She was not even beginning to grapple with the severity of the trauma she had just experienced. There was a meeting with Parks Canada staff, RCMP were present to take statements, and a victim support specialist was brought in from Golden.

Kloet recalls overhearing a person say the day’s events were an “act of God” and nothing could have been done to change the outcome.

“It was with those words that I began to shake,” she said. “Every cell in my body reverberated.”

A subsequent meeting following the avalanche, all guides involved in the rescue, but not all participants from the Massey's climb, were invited to attend a Parks Canada debrief, per the guides' report.

However, not being included in the Parks Canada debrief resulted in Kloet feeling sidelined and silenced in the aftermath of the avalanche that was a near-death experience for her. She was uncomfortable with the conclusions being made, and she began to question the process – or what she believed lack of process – the industry has for critical incidents like what she had just gone through.

"This was an unintentional omission and despite the Parks' good intentions, this understandably led to animosity from those who weren’t invited," the guides' report stated.

The guides' report also noted Hueniken subsequently ran her own professionally organized debrief for all the participants three weeks following the avalanche and said she offered to pay for therapy and connected in other ways with participants such as walks, dinners and ongoing talks.

B.C. coroner still investigating fatality

Immediately afterwards, the B.C. Coroner’s Service also began its investigation into Findlater’s death.

Officials with the coroner’s office confirmed with the Outlook the fatality remains under investigation. Once a report is complete, the chief coroner will determine whether or not an inquest will be held.

Under the Coroner’s Act and its regulations, the service is tasked with the responsibility of determining the identity of the person killed; when, where and by what means they died; and the classification, which can be natural, accidental, homicide, suicide or undetermined.

The Coroner’s Service also has the authority to make “recommendations to improve public safety and prevent death in similar circumstances,” according to its website.

There was ongoing communication between Kloet and Hueniken in the aftermath of the avalanche; however, Kloet said she continued to feel frustrated and sidelined. She felt that the ACMG’s lawyers and insurance company were trying to control the narrative around what happened and mitigate liability, rather than finding important lessons to share with the climbing community.

“Nobody went out that day to get hurt, least of all the guides,” she said. “But, there is a responsibility for being the professionals in the room and that is the responsibility I would like to speak to.

“As far as I am concerned, there are a lot of things that could have been done to help educate people and keep them safe that have not been done,” she added.

Kloet made the decision to pursue a conduct review process with the ACMG, as she felt that was the only way to get the accounting of the day’s events she was looking for. In the case of Kloet’s complaint against the guides, it was handled by the preliminary review committee and three remedies were proposed. The preliminary review committee wrote in its decision it “wishes to stress that it has not determined whether a breach of the code of conduct occurred.”

The three remedies for the guides were: to undertake avalanche rescue training with clients prior to embarking on a guided ice climbing trip, or ensure each client has received similar training within the last month; and to adopt a process for a formal written guides’ meeting agenda prior to a guided trip; and that guides adopt a technique or strategy to secure safety equipment when in avalanche terrain and there is a chance for it to be lost all at once.

“The preliminary review committee also notes that there is no certainty that additional available probes and shovels would have affected the outcome of this tragic accident,” stated the committee’s findings.

Guides, survivor, ACMG, Parks Canada reports on avalanche made public

The conduct review process does not require a complainant to agree with the proposed remedies for the matter to be considered dealt with. The process was another source of frustration for Kloet, who didn’t feel that it delivered the transparency and accountability she wanted. The conduct review process, on top of the trauma the guides were also dealing with, delayed the final report from the guides on the day’s events. It was released 18 months after the avalanche.

“This avalanche has deeply shaken many who work in avalanche terrain: low probability, high consequence events are every climber’s nightmare,” stated the report.

The report identified seven areas for the guiding community to learn from. It included insights into evaluating acceptable risks in this kind of terrain and human beings are imperfect in their ability to assess the probability of an outcome. It looked at the cumulative factors of changing conditions on the terrain and, in particular, the wind loading that occurred at a high elevation, but was not detected at the valley bottom.

The guides’ report looked at when the avalanche occurred, the rescue equipment was unsecured in backpacks and buried, which played a significant factor in the speed of the rescue. However, the report suggested if the climbers had been wearing their packs when the avalanche occurred, “there is a high probability many more participants would have been swept away.”

The report looked at discussing and practicing potential scenarios prior to a climb, and noted since the Massey incident, additional time for companion rescue training prior to climbing in avalanche terrain has been encouraged.

“The tension of balancing client desires for learning and experience and their value for the day, with an environment that has inherent risks, will always be an imperfect goal for guides,” stated the report.

Finally, the guides’ report called for a post-incident response process, not just for individual ACMG guides, but also for smaller guiding companies in the industry.

“There were, unfortunately, few resources and little emotional or mental ability to figure out what was best for the group members and how to look after everyone’s post-accident problems,” stated the report.

Paradis said since the avalanche, he has not been back into avalanche terrain except for three occasions when it was required of him to take part in required training. He has struggled in the aftermath with the loss of someone that was under his care.

“That scared the heck out of me, this incident,” he said. “I have been left with a lot of wonder about what I am going to do with my career. I have stepped back from guiding a little bit.”

Board said the day’s events have shattered many of the good things guiding meant to her and brought a lot of sorrow and anguish to all involved.

“There was a lot of shame that made me question if I should resign from guiding in the beginning; it still comes and goes,” she said. “I spoke to a lot of colleagues and spent a lot of time sifting through the decisions I made. I was encouraged to keep guiding and take on things that were comfortable.

“Although I have guided in avalanche terrain again, I often avoid terrain as much as possible and avoid serious trips.”

When Board does guide now, she talks to her clients about the inherent risks and choices of enjoying the mountains, and how she is going to create a positive experience for them in a place that can be hazardous, as well as how those hazards will be managed. She has also worked with mentors to help her process what happened and find a path toward forgiveness.

“I always respect that others have the right to their opinions and a right to process their own personal experiences, and it is not my place to judge others for judging,” Board said. “I do understand this is an approach that works for me and I have very little control over other people’s feelings.”

In addition to the guides’ report, Parks Canada produced a report on the avalanche, and the ACMG’s legal counsel contracted Alpine Solutions to conduct an investigation as well. These reports have been made public. In an effort to put together the incident review she thought should happen, Kloet contracted Viristar Risk Management Services to undertake that work. It made 14 recommendations, including a mandatory internal and external review of these types of incidents, and the ACMG should support those processes.

Viristar recommended that systems thinking principles should be applied to the development and application of procedures that make up an incident review process. It also spoke to the need for counselling and support post critical incident, for the clients and the guides involved.

The report also called for compulsory regulation of the industry if it cannot effectively regulate itself. That includes the creation and maintenance of a centralized database for collecting and analyzing – anonymously – these types of incidents, with incentives to drive high levels of voluntary participation.

The United Kingdom and New Zealand, for example, have national outdoor recreation safety legislation that sets safety standards and requires external safety audits.

“Research suggest that government regulation may be more effective than voluntary self-regulation at the individual organization or industry-wide level,” wrote Viristar in its report. “While many in outdoor recreation prefer self-regulation, well-crafted government regulatory solutions can be more effective than pure self-regulation in ensuring all providers meet reasonable standards for risk management.”

But there are those in the guiding community who take issue with how Kloet has gone about questioning the events of that day. The way she has expressed her frustration with what she sees as a lack of accountability has been seen as an attack on the guides involved.

When Kloet was trapped in the snow, she texted Margo Talbot, who travelled from Canmore to Field to support her friend.

Talbot, a veteran ice climber, said there are systemic cultural and structural issues when it comes to critical events during guided trips in the mountains. It is multi-faceted and complex. This particular incident was the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back for Talbot, and she felt the need to support Kloet and speak out.

She said there is a need for the industry and the ACMG to overhaul how it responds to these types of situations. That includes the establishment of a post-incident critical analysis of guiding incidents, as well as a protocol for guides and clients involved in these situations to receive support through counselling and a return-to-work process.

“I think for the most part, the ACMG guides today do a really good job,” Talbot said.

“Because the repercussions are so dire in the mountains, that is why it is important to listen to everyone’s voice."

The guides' report highlighted the difficulty in understanding the lessons from the day of the avalanche, noting "All those affected have experienced extreme trauma and grief, and learnings in these situations take time and reflection, and require humility and compassion."

Hueniken has remained close with Findlater's family and continues to share important moments with them such as birthdays, anniversaries, visits with her husband, nieces, friends and parents.

"Sonja was incredible, and I am reminded daily just why she was. ... This is what continues to inspire me. If I could give up every day of guiding and climbing in my life to have that day back, I would. But I can't. I can’t change the outcome of that day, and I can’t change anyone's perception or feelings towards it. I can only affect how I move forward and what I can offer my family and my community."

Hueniken said "a lot of circumstances coming together" led to the tragic result of this event, but expressed hope for coming changes.

"The industry has and will change from this accident and we are all still taking away learnings," she said. "The emotional insights however have been the most significant for me. Everyone deals with loss and grief and trauma differently."

Mental Health Supports

- Mountain Muskox: www.mountainmuskox.com

- Mental Health Helpline: 1-877-303-2642

- Addiction Helpline: 1-866-332-2322

- HealthLink: 811

- Urgent mental health walk-in services are available at the Canmore General Hospital and Banff Mineral Springs Hospital seven days a week 2-9 p.m.

- 211 Alberta

- Bow Valley Addiction and Mental Health: 403-678-4696

PART FOUR OF BURIED IN THE AFTERMATH WILL LOOK AT THE PROGRESS THE ACMG HAS MADE DEVELOPING A POST-CRITICAL INCIDENT PROCESS FOR ITS MEMBERS AND HOW GUIDING COMPANIES REPORT FATALITIES OR CRITICAL INCIDENTS.

IT WILL ALSO TAKE A LOOK AT HOW MANY FATALITIES HAVE OCCURRED ON KNOWN GUIDED TRIPS IN THE BACKCOUNTRY SINCE 2000.

CORRECTION: In part three of Buried in the Aftermath it was incorrectly reported that Will Gadd did a risk assessment the night before the avalanche at Massey's Waterfall. He contributed to the avalanche forecast, but did not do the risk assessment. It was also incorrectly reported a conversation between Sarah Hueniken and Margo Talbot four days prior was specifically about the Massey's route.

The Outlook apologizes and regrets these errors.

(1).png;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)