First Nations and Métis in Alberta are joining with environmental organizations to formally request that Ottawa add a hazardous toxic acid found in oilsands tailings ponds to the Canadian Environmental Protection Act (CEPA).

The proposed change would impose more stringent regulations, monitoring and restrictions on naphthenic acids, which are listed as hazardous substances in the United States.

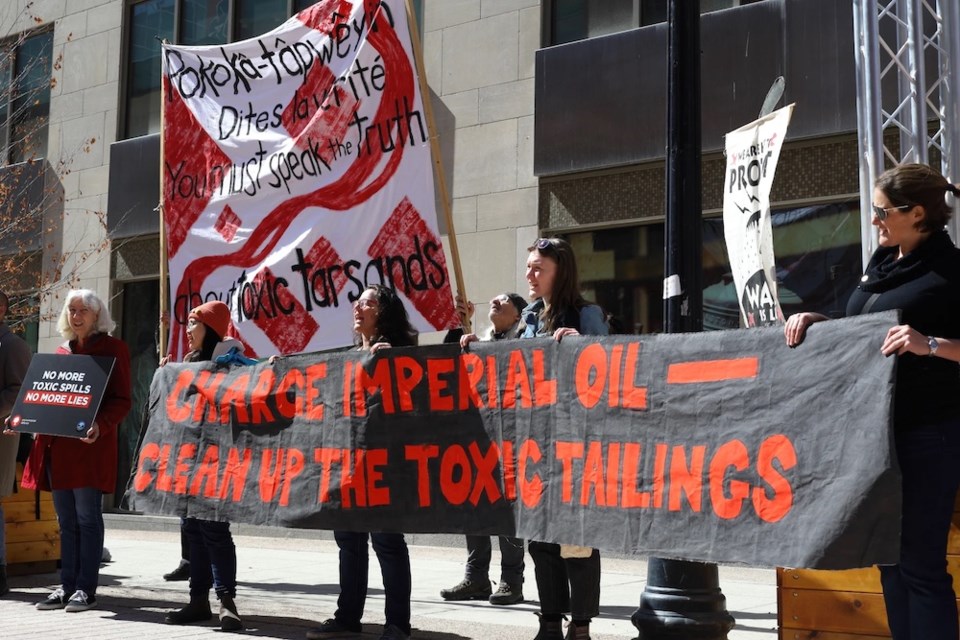

Ecojustice filed the formal request on behalf of the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation, Environmental Defence and Keepers of the Water.

In 2022, a leak of 5.3 million litres of polluted water from the oilsands tailings ponds impacted downstream communities. It was one of the largest spills in the province’s history. But it took Imperial Oil and the Alberta Energy Regulator months to tell First Nations downriver about the pollution release.

Jesse Cardinal, executive director of Keepers of the Water, said regulation of the acids is urgent given the proposed plans to release tailings water into the Athabasca River after treatment. Even after industry treats the tailings water, it still contains high levels of naphthenic acids, Cardinal said.

Naphthenic acids, which accumulate in oilsands tailing ponds, have been found to harm fish and amphibians. There are still gaps in research about possible impacts on human health but the acids are a potential endocrine disruptor, which can affect hormone functions in people, according to the press release. However, Cardinal believes the chemical could be related to disease in fauna of the region and high rates of rare cancers within Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation.

Cardinal argues that Ottawa must assume a bigger role in curtailing what she describes as a toxic crisis in First Nations in northern Alberta. She points to the Crown’s treaty obligations and suggests the province puts no value on the environment.

“They have a duty to consult, but they also have a duty to ensure that water is being protected for future generations,” she said, referring to the federal government.

The formal request about naphthenic acids is possible after the modernizing of CEPA, which allowed civil society to ask for an investigation of a substance, said Aliénor Rougeot, program manager of climate and energy at Environmental Defence, in an interview with Canada’s National Observer.

Ottawa can unlock its tool chest of regulatory mechanisms if naphthenic acids are found toxic, Rougeot said, including the creation of emergency plans during leaks or security deposits on industry.

However, legal experts, who consulted with Environmental Defence, warned there is a risk if Ottawa rules naphthenic acids toxic that regulation could be weak and perhaps only require increased self-monitoring, Rougeot explained.

Environmental health experts have sounded the alarm over Ottawa's lack of investment in environmental health. Last summer during the wildfire crisis, health experts published a paper calling for a new environmental health institute and more research funding.

Currently, Canada's environmental health research is funded through a hodgepodge of institutes that examine such issues as cancer, aging and Indigenous Peoples’ health, among others. Meanwhile, the United States National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences has been running since the 1960s.

Ottawa’s funding lags behind other western jurisdictions, even when measured at a per capita rate. Canada is investing $37.5 million in environmental health research compared to roughly $1.3 billion in the United States, and roughly $3.6 billion in the European Union, according to a recently published paper calling for an environmental health institute.

“One of the things that has struck me the most as I've been working on the issue of tailings is how the government has readily accepted the absence of evidence as evidence of no harm,” she explained.

Experts and front-line communities near the oilsands have been advocating for studying the cumulative health impacts of oilsands tailings since 2003. An initial proposal was submitted to the federal government in 2019, however, the requests have gone unfulfilled.

There are around 1.5 trillion litres of tailings in the oilsands, which Rougeot estimates is around 2,000 times the volume of water in Lake Louise, the picturesque lake in Alberta’s Rocky Mountains.

Rougeot estimates it could take months or even years before a decision is made to regulate naphthenic acids.

“Not a month goes by without news of someone else becoming sick or dying,” Allan Adam, chief of Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation, said in a press release about the formal request.

“I don’t know how much more of an alarm we have to raise before Canada takes its obligations to protect our health seriously.”

— With files from Natasha Bulowski and John Woodside

Matteo Cimellaro / Canada’s National Observer / Local Journalism Initiative