BANFF – Bears, cougars and wolves consistently navigate the busy Banff townsite through an important and already compromised wildlife corridor north of the train tracks where there are plans for a massive paved parking lot, according to the latest data provided by Parks Canada.

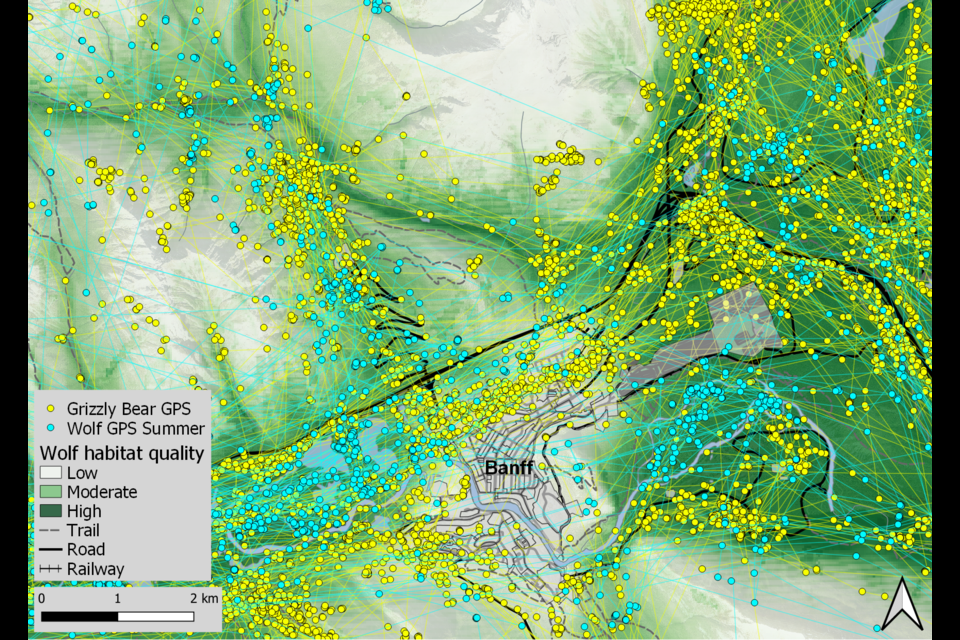

Parks Canada has publicly released data maps on the movements of 34 GPS-collared grizzly bears and 33 collared wolves skirting the townsite spanning 20 years from 2000-20 and winter tracking of wolves and cougars from 1993-2017.

The maps show the Fenlands-Indian Grounds wildlife corridor north of the train tracks – including an area earmarked for a 600-plus stall intercept lot near the Fenlands recreation centre as part of Liricon Capital’s redevelopment plans of the railway lands into a multi-modal transit hub – is heavily used by wildlife.

Parks Canada wildlife experts – who can’t speak to the development and only effectiveness of corridors – say data for the last few years is still being compiled, but believe the trends of animals using the wildlife corridors around town won’t look much different than they have since the mid-1990s.

“I can say this Cascade, Fenlands, Vermilion Lakes corridor is important for wildlife,” said Jesse Whittington, a wildlife ecologist for Banff National Park’s ecological integrity monitoring program.

One of the biggest motivators of wildlife movement, particularly for bears as they seek to put on weight ahead of hibernation is food, but Whittington said wildlife movement is also influenced by human activity.

“As you layer roads and towns and trails and human use on all these features, they have cumulative effects on wildlife,” said Whittington.

“Human activity on one trail might not have a big effect on wildlife, but when you add these other developments on there, it can make it increasingly difficult for wildlife to use some of these areas.”

Banff town council hasn’t removed the proposed north side parking lot from the area redevelopment plan (ARP), preferring to rely on the results of a federally legislated impact assessment to consider positive or negative environmental consequences, and possible mitigations, including a look at the ARP’s implications to the wildlife corridor.

Simply put, a wildlife corridor is a route that allows wildlife to move safely between areas of suitable habitat. In the Banff area, corridors are typically narrow, funnel-shaped tracts of land between the developed areas and the steep mountain slopes.

Parks Canada has consistently monitored wildlife movements of the key corridors around the townsite since the early 1990s. There are now 25 established winter transects – essentially a straight line that cuts through the landscape so standardized observations and measurements can be made – which are checked 10 times each winter as part of the agency’s baseline ecological integrity monitoring program.

Whittington said they look at the proportion of time that carnivores – wolves and cougars namely – are detected travelling across these transects, and compare how wildlife move in corridors versus the less disturbed landscapes like the Fairholme benchlands to the east or Hillsdale to the west.

Cougar and wolf tracks were picked up about 50 per cent of the time on the less disturbed transects and about 30 per cent of the time in the corridors, he said.

“What we’ve seen is that wolves and cougars use corridors around town pretty consistently for the last 14 years, however, they move through these corridors less than the surrounding, more intact landscape,” he said.

Whittington said this monitoring work is done to make sure wildlife corridors are still functioning.

“Wildlife movements are compromised in these areas, but we want to make sure animals can still travel through these areas because connected wildlife populations are more resilient and more likely to persist over time,” he said.

When wolves and cougars are detected on these transects, Whittington said there is sometimes time to follow their paths through the snow.

“We can backtrack them, so we make sure we’re not disturbing them,” he said.

“We can see in a fine-scale way how they travel through this landscape, where they encountered prey, what did they kill and what did they eat.”

Conservationists have called on Banff council to oppose any development on the north side of the tracks, arguing the addition of another 400 stalls as part of an expansion of the existing Fenlands parking lot would compromise an already narrow travel route in the Fenlands-Indian Grounds wildlife corridor.

Yellowstone to Yukon (Y2Y) Conservation Initiative, which strives to connect and protect enough space for a wide range of species to roam, feed, and reproduce, opposes the addition of another 400 parking stalls on the north side of the tracks.

Adam Linnard, Y2Y’s manager of landscape protection, said the gravel bed floodplains at the bottom of the Bow Valley are immeasurably important to wildlife at a continental scale, noting there are few valleys in the entire Rocky Mountain chain allowing east-west movement at low elevation with rich food.

He said within and beyond Banff National Park, infrastructure and transportation development has seriously compromised this essential ecological function, but designating and protecting wildlife corridors like the Fenlands-Indian Ground corridor prevent “totally severing wildlife connectivity.”

“When a grizzly bear, wolf, cougar, or elk struggles to find their way around the town of Banff, that adds additional strain to a stressed population that needs to maintain genetic links across hundreds or thousands of kilometres in order to maintain its viability in the long term,” he said.

“For that reason, a relatively small parcel of land between the railroad and the highway plays an integral role in maintaining wildlife populations between the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem and the Arctic Circle. We need this network to persist.”

Bow Valley Engage (BVE), which doesn’t want to see development compromise functional wildlife corridors throughout the Bow Valley on provincial lands and in Banff National Park, says the history and preservation of this particular corridor dates back decades.

BVE’s Leanne Allison said the function of the corridor north of the railway tracks and east of the Norquay interchange was identified as a concern as far back as the 1984-88 twinning of the Trans-Canada Highway between Cascade and Sunshine interchanges.

She said upgrading the highway included several kinds of wildlife underpasses, along with fencing to improve wildlife safety and movement.

Allison said the redevelopment plan for the railway lands contradicts decisions and changes that have occurred during the years since the highway was twinned through the area, such as closure of the airport cadet camp and bison paddock and relocation of the old wildlife lab and horse stables.

“All these changes were done to enhance access and travel through the area by wild animals,” she said in a letter to Banff town council ahead of the March 20 public hearing on the ARP.

“The proposed ARP is a threat to wildlife travel and habitat use.”

Allison said science shows effectiveness of all the corridors in the Bow Valley depends on every one of them functioning to their greatest capacity.

“They are all important for regionally healthy wildlife populations,” she said.

Currently, the ARP calls for vegetation to enhance the sand dune as a natural berm to guide animal travel around the Fenlands recreation centre, as well as restoration of 0.93 hectares of brownfield industrial lands to a naturally forested state, and enhancements to the existing 4.3-hectare vegetated area.

Council has also pressed for changes to the phasing stages of the ARP to move up rehabilitation of the conservation area on the north side of the tracks to within five years of adoption of the ARP, instead of 10 years out.

Jan Waterous, Liricon’s managing partner, said as part of the work over the past six years to advance opportunities to reduce the impact of personal vehicles on the national park, environmental experts were consulted to assess how intercept parking, aerial transit and passenger rail can enhance wildlife corridors.

She said the ARP is a high level planning document, which is a first step towards transforming the railway lands into a multimodal transit hub to reduce the need for personal vehicles in town and the surrounding park and “thus enhance wildlife corridors.”

The ARP includes an extensive section on the environment conducted by Golder and Associates, Waterous said, which identifies the opportunity to enhance the Fenlands-Indian grounds wildlife corridor by restoring 5.4 hectares of brownfield area north of the railway tracks.

“Following full approval of the ARP, the next step will be to advance specific projects which will include studies that determine the opportunities for projects that will enhance wildlife corridors and their accompanying mitigations,” she said.

“Of note, our efforts represent the largest land mass ever set aside by a private operator to enhance wildlife corridors in Banff National Park history.”

“Imagine if you’re a wolf out near Johnson Lake, the most likely area you’re going to come through is that Cascade corridor just below Cascade Mountain – that’s an incredibly important area for carnivores,” said Whittington.

“And what’s great is they sometimes predate on deer and elk in that area, so the most effective corridors are ones where animals are both travelling through, but then they can also feed and forage and rest in those areas.”

As animals approach Forty Mile Creek, Whittington said their movements become constricted near Stoney Mountain on the north side of the Trans-Canada Highway.

He said animals can cross to the south side of the highway via two underpasses and move between the highway and industrial area.

However, he said the one at Forty Mile Creek can be difficult to get through in summer because of high water flows.

“Then as they approach the west entrance to Banff, it’s a pretty busy area, but wildlife still zip through that area out onto Vermilion Lakes,” said Whittington.

“In winter they can travel across the lakes because the water is frozen, but in summer, again, their movements are a little bit more constricted and they need to follow firm ground to the west.”

If wildlife stays on the north side of the highway, Whittington said the data shows “travel is pretty good” until they get about one kilometre west of the Banff townsite’s west entrance.

At that point, he said the topography changes, forcing wildlife to go up and down steep terrain and ravines to move through there, which takes up a lot more energy for them.

“You can see on the snow tracking maps that they do in fact move there,” said Whittington.

“But if you compare the GPS data map and the snow tracking map, the GPS data shows many more movements on the south side of the highway and along Vermilion Lakes as they move west.”

On the south side of the Banff townsite, Whittington said wildlife head south from the Trans-Canada Highway along Tunnel Mountain, or over by the golf course, where their movements become restricted again.

“There’s a really narrow area between the Bow River and Rundle Mountain that they have to nip through and then can either travel up the Spray Valley or they can keep going around Sulphur Mountain to the west,” he said.

“We have that permanent closure in the Sulphur area to facilitate wildlife movements to those areas.”

Parks Canada also uses data from an extensive remote camera network as another non-invasive way to monitor wildlife movements throughout the Bow Valley and Banff National Park.

“It again shows we have wildlife moving through these corridors, but for species like grizzly bears and wolves, we find we have higher detection rates out in the broader, more intact landscape compared to detection rates closer to Banff townsite,” said Whittington.

A 2022 study, Towns and trails drive carnivore movement behaviour, resource selection, and connectivity, by Whittington and other wildlife experts, looked at grizzly bear and wolf movement through Banff, Kootenay, Yoho national parks and the surrounding landscape over a 20-year period.

A key finding in the peer-reviewed study that was published in Movement Ecology was grizzly bears and wolves increase the speed of travel near towns and areas of high trail and road density, and avoid feeding and resting near developed areas, thus reducing secure habitat for wildlife.

In addition, the study concluded the current development cuts the amount of high quality habitat in the Bow Valley by 42 per cent from baseline pristine conditions, and human development reduced wildlife connectivity by approximately 85 per cent compared to those pristine conditions.

Whittington said other previous research has shown wildlife avoid areas with people but also areas adjacent to people.

“People have an effect on wildlife beyond our footprint on the landscape,” he said.

Overall, in terms of the wildlife corridors, Whittington said it can be challenging for animals to currently move around the Banff townsite, but they can still manage it.

“To me, it’s promising that animals are still travelling through these corridors both on the north and south side of Banff,” he said.