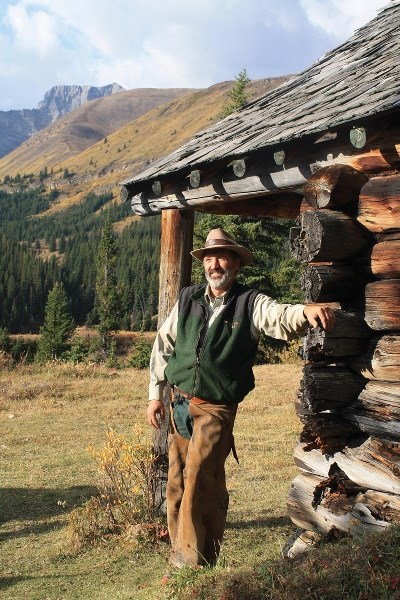

BANFF – In 1964, Cliff White lit his first fire as a nine-year-old kid.

His father had some early insight into his interests during a criminal investigation of his son’s first prescribed burn.

“A group of us Banff kids, while playing with matches, set the forest alight on the side of Sulphur Mountain,” said White.

“We could have easily destroyed the newly built Sulphur Mountain Gondola without the intervention of a fast thinking group of park wardens. Dad couldn’t believe I could go on to make a career of this.”

In fact, White has recently been given a prestigious award for his work in conservation during his almost four-decade career with Parks Canada, including his leadership in fire management.

The Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society (CPAWS) handed White the J.B Harkin Award, named for Canada’s first national parks commissioner, James Bernard Harkin, who developed the idea of conservation in Canada at a time when there was little precedent.

Alison Ronson, CPAWS’ interim national executive director, said White took his ideas about science and ecosystem management into practical solutions on the landscape.

“For his dedication to conservation and Canada’s protected areas, CPAWS recognizes Cliff and his life’s work,” she said. “In Banff National Park, Cliff exemplified the concept of ecosystem management. He understood the complex interactions within and between ecosystems.”

White, who helped launch Parks Canada’s prescribed fire program across the country, said he was honoured.

“It was really fun for me,” he said, noting he went to Ottawa to receive the award. “If you grew up in the Bow Valley and worked in the Bow Valley, you know people who have gotten the Harkin award over the years.”

CPAWS praised White for his work alongside elders of the Stoney Nakoda First Nation to help make possible the signing of the 2010 Letter of Understanding with the Stoney Nakoda, welcoming them back into their own homeland.

His work to set up Parks Canada’s prescribed fire program was also

recognized.

“White helped Parks Canada become a global leader in prescribed fire management,” said Ronson. “Provincial agencies, Australia and other countries now regularly call on Parks Canada’s fire specialists in managing fire regimes.”

In the 1990s, a large elk population centred around the Banff townsite was raising public safety concerns, but White’s work contributed to understanding that the large elk population was also eliminating aspen and willow - and with them beaver, songbirds and moose.

“The entire ecosystem was out of balance,” said Ronson.

White started with Parks Canada in 1973 as part of a joint trail and fire crew working in Yoho National Park. He became a park warden in 1975 and retired in 2009.

“I’ve had a very varied career, but I’m probably publicly most known for work in fire,” he said.

In fact, White fought with those who did not see the big picture and the kinds of radical changes that needed to happen in fire management. At one time, the door to his office had a sign that read: “job description for a civil servant: tell the truth and obey the law.”

In 1986, White was sent to Ottawa tasked with getting a national fire program in place. He was there until 1990.

“We knew we couldn’t sustain a park here, a park there, without really having some kind of regional recognition that we had some competency in managing fire as an organization,” he said.

“We just couldn’t do prescribed burns in Banff unless you had that credibility, so we set up a system where we very quickly built a national system.”

Within three years, fire teams were created and quickly gaining experience in prescribed fires.

“In a decade they were burning from coast to coast,” said White.

Today, White said fire management is one of the biggest challenges.

He said there have been great advances on the state of wildland fire management in North America, but that’s difficult to recognize during last year’s disastrous California fires.

Many people have lost their homes, their livelihoods, and even their lives to fire during these difficult times, he said, noting there are however signs of progress, such as saving Waterton Lakes townsite from burning during the 2017 Kenow wildfire.

“It’s not just human habitat suffering from poor fire management, it’s the habitat for most native species across the landscape,” he said.

White said the big lesson of all these tragedies is the firefighter’s lament – you can’t put fires out, you can only put them off to a hotter, dryer day.

“Sooner or later almost all wildland or semi wildland landscapes will burn, and we must manage ecosystems and our own activities to recognize this, just like First Nations have done for many millennia,” he said.

“There is still too much left to chance, not to good planning.”

The right fire management mix includes FireSmarting and fuel breaks, and lastly, regular prescribed burning, said White.

“We need to relearn the age-old techniques of First Nations to light fires at appropriate times, and burn routinely as part of living with the land,” he said.

“The adage of most park and forest managers should be to ‘burn early, burn often’ to follow this traditional knowledge.”