BOW VALLEY – Increases in human activity and development threaten wildlife populations around the world.

A new interagency study shows wildlife connectivity for wolves has decreased in the Bow Valley by 25 per cent and for grizzly bears by 21 per cent since historic, pre-development times.

According to the study, Towns and Trails Drive Carnivore Connectivity using a Step Selection Approach, connectivity will decrease a further six per cent with proposed expansion of Canmore, including Three Sisters Mountain Village (TSMV) developments, which could double the town’s population in 20 to 30 years.

“The landscape of the Bow Valley is already very degraded for wildlife movement,” said Mark Hebblewhite, one of the study’s authors and a professor in the wildlife biology program at the University of Montana in Missoula.

“We found if Three Sisters builds out and the town of Canmore has a whole bunch of new development, we’re going to see an additional six per cent reduction in connectivity.”

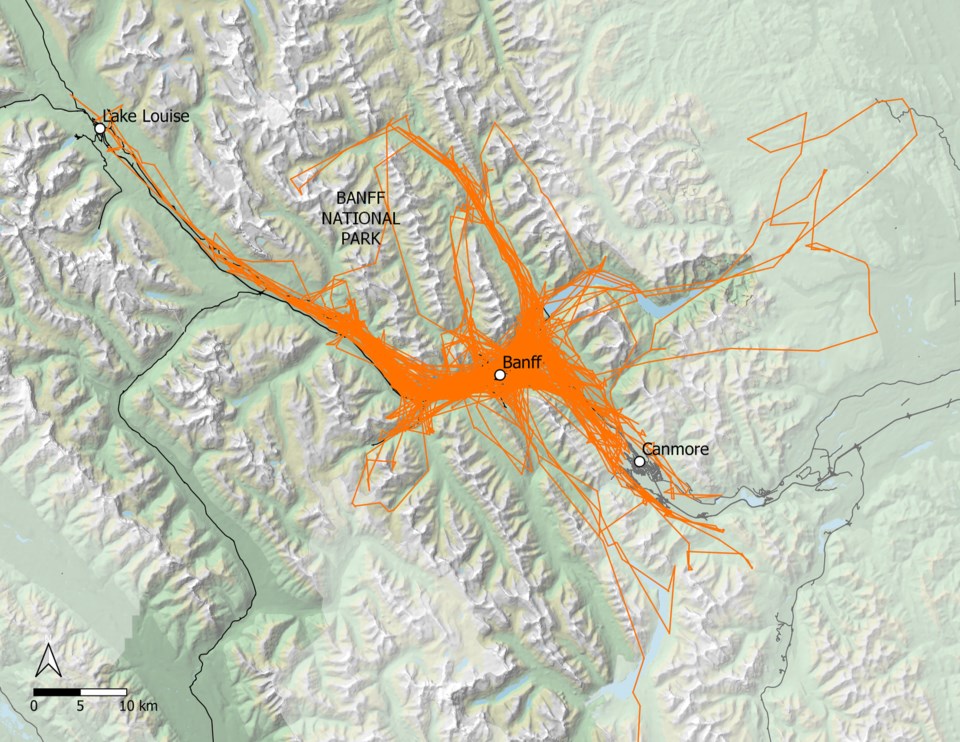

Researchers analyzed GPS data from 34 collared grizzly bears and 33 collared wolves using 150,000 GPS locations from 2000 to 2020 in a 17,500-square kilometre study area within and adjacent to Banff National Park.

Like many global protected places and bordering communities, human activity within the study area increased steadily over the last 20 years. Banff gets about 4.1 million annual visitors, and Kananaskis Country saw record visitation of 5.4 million last year.

The Bow Valley, which links these two areas for wildlife through Canmore, is critical in the Yellowstone to Yukon (Y2Y) Conservation Initiative – and is one of just four east-west connections in the entire 3,200-km Y2Y region.

Within an animal’s home range, effective wildlife corridors are considered vital, and are used by animals for different reasons such as dispersal, migration, foraging or mating.

The research paper emphasizes wildlife corridors provide vital movement for animals, large and small, in areas that are greatly constrained by infrastructure and steep mountain terrain.

“The ability of carnivores to move from one area to the other is already compromised here,” said Hebblewhiite, who sat on Alberta Environment and Parks’ 2018 external science review panel looking at corridor guidelines for the Bow Valley. “And it’s going to get worse.”

Using a new method to estimate connectivity, researchers simulated movement paths for wildlife based on three landscape scenarios – historic conditions with no development, current conditions and future scenarios.

To do the latter, they modified Canmore’s developed footprint to reflect residential and commercial development proposals in Three Sisters. The footprint of Banff, on the other hand, is legally fixed in federal legislation.

With the results of the study, Hebblewhite likened wildlife trying to get around the busy Bow Valley to a pinball machine.

“When you see the movements of radio-collared wolves or grizzly bears trying to navigate the areas around Banff or Canmore, what I often think about is pinball machines, but sort of in reverse – gravity is always pulling the ball down, but there are so many obstacles in the way, the ball can’t always get there,” he said.

GPS data shows a wolf known as No. 2001, which was fitted with a tracking collar in Banff National Park last year, travels extensively throughout the Bow Valley, from Lake Louise to Canmore.

The tracking information shows the sub-adult male wolf has spent more time in the Canmore region than any time previously over the past six months, crossing through the south side of Canmore seven times and north side on four occasions. (This wolf was shot and killed by a rancher in Montana on March 8.)

Hebblewhite said proposed developments at Three Sisters, which would extend east to Dead Man’s Flats and Wind Valley, will have a big effect on wildlife movements like those of wolf 2001.

“The likelihood of these sorts of movements through the valley, successfully, as part of daily lives of wolves in the Bow Valley, or wolves dispersing through the Bow Valley, are going to be quantitatively and measurably reduced in the future with an expanded Three Sisters footprint,” he said.

Hebblewhite said wildlife trying to get through the Bow Valley are often looking for big patches of high quality habitat. They get pulled to the lower elevations, where buildings, roads, fences and developments block them.

“Eventually, they often get killed on roads or railways, get into trouble with humans, or get through – those are the three options for wild animals,” Hebblewhite said.

“Adding more development to the landscape means the number of successful pinball games, from the animals’ viewpoint, declines and more and more animals give up and fail to access those higher quality habitat patches – or die.”

The research showed carnivores avoided areas near towns in all seasons and avoided areas of high trail density with lots of mountain bikers, walkers and other recreationalists.

In addition, the study shows developments and human activity reduced the amount of available high quality habitat for large carnivores by an average of 14 per cent under current conditions and 16 per cent under future conditions.

“The corridors themselves are pinching off animal movements, but it is also the reduction of habitat quality that animals need to live in,” Hebblewhite said.

Jesse Whittington, a Parks Canada wildlife ecologist with Banff National Park, was the lead author of the study. He was forbidden by Parks Canada from speaking on his research paper; however, the federal agency did email a statement.

Parks Canada pointed to work in Banff National Park to improve wildlife connectivity, such as highway underpasses and overpasses, permanent closure of a wildlife corridor near Middle Springs and seasonal closure of the Bow Valley Parkway.

Justin Brisbane, a spokesperson for Parks Canada, said the lessons learned in Banff have been applied around the world for developing safer travel corridors for people and animals.

“Effective use of wildlife corridors is essential to ensuring a healthy and resilient ecosystem,” he said.

While several wildlife corridor papers have been published pertaining to Banff National Park, Brisbane said this research provides a quantitative estimate of corridor effectiveness, which has been lacking from previous research.

“This interagency paper will help address corridor and connectivity issues discussed in the 2018 recommendations for improving human-wildlife coexistence in the Bow Valley report,” he said.

Adam Ford, one of the authors of this study and assistant professor and Canada Research Chair in wildlife restoration ecology at the University of British Columbia’s biology department, released a separate paper last September on wildlife corridors.

Ford has been working on wildlife corridors in the Bow Valley since 2006 and said width is one of the most contentious dimensions of corridors because it often limits industrial, residential, or recreational expansion.

He noted the effectiveness of wildlife corridors in the Bow Valley are already compromised by human activity and infrastructure within and adjacent to designated wildlife corridors. He said the safe movement of wildlife through the Bow Valley can be successful if several mitigation measures are considered.

“They include increasing the width of corridors, reducing human activity within corridors, improving movement beyond the corridor, and minimizing sensory disturbance adjacent to corridors,’ he said

Along with Hebblewhite and Whittington, other authors of the newest study include Banff National Park resource conservation officer Robin Baron and Alberta Environment and Parks biologist John Paczkowski. The paper is posted on bioRxiv and has been submitted to the Journal of Ecological Applications for publication.

“There are measurable reductions in connectivity for grizzly bears and wolves,” Hebblewhite said. “More development is going to be the final nail in the coffin for wildlife movement.”