Why did the grizzly bear cross the road?

Perhaps to find a mate, but a recent WildSmart talk focused more on how the grizzly bears and other southern Alberta wildlife have been crossing the road for the last three decades thanks to wildlife crossing structures.

“The impacts have gone beyond North America,” Tony Clevenger, wildlife research scientist explained at the presentation earlier this month. “Information [has been] used from this research to build the most ecological sustainable highways across the world.”

The success of Banff National Park’s wildlife crossings over the Trans-Canada Highway has inspired other countries to follow suit, according to Clevenger who first spoke about the importance research played in understanding the effects of the crossing structures.

“People didn’t know if the crossing structures really worked,” Clevenger said with a laugh, noting that after five years of Parks Canada funding research, the Woodcock Foundation stepped up to continue funding insights into the innovative project.

For the first five to six years, researchers would physically go and check the overpass and underpass track pads every three days before they started using cameras.

The researchers found it was better to use cameras in the long-term to decrease human use and allow for the wildlife to travel through unencumbered.

“You need good data to inform the transportation agencies ... if we would have only studied for two years, we would have suggested more and bigger structures versus our five-year research,” Clevenger explained.

With the introduction of DNA science, researchers started grabbing hair samples to dive deeper into which animals were utilizing the mitigation structures. Installing barbed-wired fences and “rubbing trees,” the researchers were pleased to find out the new wires did not deter the animals crossing while also giving the team a deeper analysis.

“The results were really impactful,” Clevenger said.

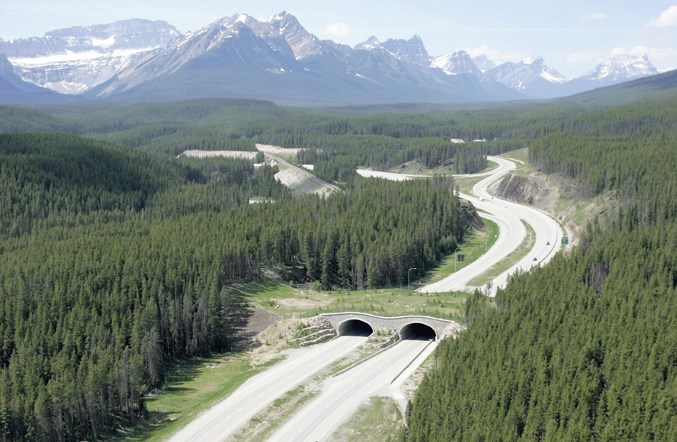

Now with the 38 wildlife underpasses and six overpasses from Banff National Park to the border of Yoho National Park, other countries could not deny the years of research showcasing the benefits of these mitigation structures, including the cost benefit.

With an estimated $200,000 cost savings a year, Clevenger explained the cost of a collision varies depending on the animal but regardless is very high, for example it would be an estimated $7,000 for a collision with a deer, $15,000 with an elk and $30,000 with a moose.

“In four years we found there was no wildlife vehicle collisions on the parts with mitigation,” Clevenger said.

With the increasing proven benefits through research, other countries started

taking notice.

Since the 17 years of research Clevenger put into the Banff wildlife mitigation crossing structures, the wildlife research scientist has toured the world speaking with other countries about how they can implement mitigation development for their native species, like monkey bridges for example.

The wildlife crossing in Costa Rica, in a partnership with Refuge for Wildlife, Nosara Civic Association, Costas Verdes and Harmony Gardens, is working on installing rope bridges and planting trees rich with food resources to relink existing green spaces after noticing a decrease in the howler monkey population and other arboreal wildlife since the increase in deforestation for development.

That is just one of the 12 wildlife mitigation projects in Costa Rica, what Clevenger described as one of the “most progressive” countries in Latin America in regards to wildlife co-existence practices.

Other countries implementing, or looking into building crossing structures for wildlife, include Mexico, Brazil and Argentina.

According to a long-term monitoring of wildlife crossing structures in the Atlantic forest study, the increasing paved roads in the Misiones province of Argentina was affecting the threatened jaguars and tapirs, leading to a five-year research project with 28 species of large and medium-sized animals recorded in the seven wildlife crossings.

Clevenger shared a personal anecdote of touring through Iguazu, Argentina when he asked the project developers what inspired them to build an overpass.

“Because Banff has one,” Clevenger said with a laugh.

The end of the Argentina study stated they needed more long-term monitoring for better planning for mitigation measures for Latin America roads – a point Clevenger has been trying to get across since 1996 when his research first started.

“This information has been used everywhere,” Clevenger said, noting that it would not have been possible without having the long-term research from Banff in the first place.